Most of these students have never been to a wetland, never been to a river..it’s exciting to awaken these feelings.

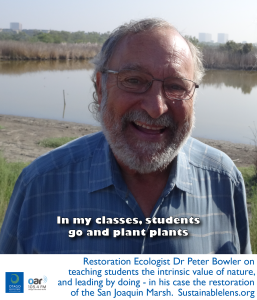

Dr Peter Bowler is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at University Calfornia Irvine. His is Director of the UCI Arboretum and Herbarium, is Faculty Manager of the Natural Reserve System’s San Joaquin Marsh and Burns Pinyon Ridge Reserves, and Director of the Interdisciplinary Minor in Global Sustainability.

Extra: Field-trip to the San Joaquin Marsh.

Talking points

I grew up by in Idaho by the Snake River, and I worshipped nature, botany, I loved freshwater biology, It stimulated me. I became very interested in snails.

I managed to get four snail species listed as endangered, I was involved in a lot of dam controversies, even described a new new genus and species in one of them.

When I was a child, it was so remote, my parents were educated luminary people in the area, so every geologist and palaeontologist passing through would stay at our house.

My role has been primarily teaching, I ran an environmental education programme here at UCI

I teach a lot, a lot more than I’m required to teach, but I enjoy teaching.

(Developed a sustainability minor in 1994 only a couple of years after Rio) Before that I was involved in global peace and conflict studies – they’re very similar. One of the things I really about both programmes is the interdisciplinarity that is emphasised – the fact that cooperation, complementarity and hearing what other people have to say…learning about other fields is very important.

One of the most exciting things is the establishment of a formal initiative in sustainability.

Ecological restoration…a massive expansion locally…I was involved in a lot of controversy.

America was a leader in environmental ethics – we need to return to that.

The original idea was conquering the west, trying to be master of nature, fighting nature, trying to control it, bringing it into utilitarian causes. And then there came a time when the American consciousness changed, people thought maybe we’ve gone too far, we need to start setting land aside, we need to start going the other way – preserving things. Modern attitudes about desert are very different from what they used to be – it used to be they were viewed as wastelands, today people treasure them.

There’s a need for cities not to be ecological deserts.

People are realising that deserts have an intrinsic value unrelated to people, and that’s a very different kind of epiphany.

Most of these students have never been to a wetland, never been to a river..it’s exciting to awaken these feelings.

You want to teach the intrinsic value of these sites – my this an area that has 273 bird species, I never knew that. Here is an area of 55 hectares of wetland that Dr Bowler and his colleagues got funding for, designed and constructed – for us and for wildlife..and if he can make a difference, I can too.

Ethical structures…land ethic.

Understanding expressions of culture has adopted. Compare the intrinsic values expressed in the Wildlife Act to a time of shooting buffalo from the train.

One of the wonderful things about sustainability at this point in time is that we can look back – we never should have built all those dams…

Sustainability: we share the planet with other organisms, and as the human population expands, and so do its needs and requirements, we have to do that in a way that does not further degrade – to the extent possible – the natural environment in which we live.

We are cohabiters with nature and life.

In my classes…(even the theory ones)…students go and plant plants.

Our urban landscapes are not restoration sites, but they can play a large role, particularly in softening the impact along the urban/wildland interface… and in providing corridors.

Restoration can’t be pure restoration everywhere, most places have been so severely damaged that you’ll never get the full complement of species, and the true goal of restoration is to do that – to bring back all of the biodiversity that existed at site using a natural model. Then ameliorating the impact of humans along the line. Expanding and connecting natural areas.

There are efforts to scale things up. While I was talking before about pure restoration maybe not being possible, it’s all worth trying. It may not be like it was when native Americans were here, but it can definitely be wild.

To me, to really be meaningful we should focus on expanding our natural areas and connect them…then native plants in urban areas to connect

It’s just about planting plants, it takes landscapes too. Today we’re going back…putting bends in the river…developing ways to hold water on the site rather than getting rid of it.

(Are roof gardens, community gardens, small scale restorations worth the effort?) Absolutely. Placement is important, but they are extremely valuable in educating students, they’re integral in having places for both resident and migratory wildlife, critical for linking habitats.

(Success) Area has had a history of grazing…the cattle had really bashed it…working with agencies I was able to get 12.5 acres preserved. We transplanted…native species…to remove non-natives, replace it with native known genetic stock, now besides the California gnatcatcher which is abundant there, there is the California coastal cactus wren which is almost extinct – and we have several pairs nesting in the cacti we have moved.

(Activist) Yes. I certainly have been in the past. Not so much marching and carrying billboards, as trying to provide sound scientific comment on management approaches, publishing, training. I consider teaching activism. Training students to be able to understand and think critically on their own.

(Motivation) I have a ridiculous number of everything to do. 748 students this past quarter. Every day I go to the marsh, and all the coyotes – we all know each other, they see me coming, we sort of salute each other, I howl at them a little bit – for me personally this has been beautifully fulfilling in my lifetime. I can show you picture of areas that had not a plant on them, and now is healthy coastal sage scrub with gnatcatchers living underneath it – I can’t tell you how rewarding that is.

(Challenges) Follow-up restoration…we have just completed removing 3,100 lineal feet of road,…my ultimate plan is to make the lower part of the marsh an area that salt marsh can migrate into, before flood control channelisation in 1968 you could row from Newport Back Bay and all the way up into the marsh…so I would to open it, so when sea level rises and we lose that 900 acres of salt marsh, we’ll be able to at least have 50, maybe 100 acres for the salt marsh for the highly endangered Ridgway’s rail. Its a salt marsh obligate, unless we do this it will go extinct. It’s very important, I’m going to get that done.

(Miracle) In the marsh it would definitely be developing the whole lower marsh as a salt marsh. I’d like to do a study of the succession that will occur as the relationship shifts between the landscape and the Pacific Ocean. In education it would lower class sizes, more interactive hands-on learning approaches will be more meaningful.

(Advice) We need to be more cautious and think really about our personal…karmas…behaviours. When I came to California in the 1970s there was so much smog, your couldn’t even see across the campus. And thanks to catalytic converters and other improvements, that’s gone. We can be little catalytic converters as well. We can make huge contributions as an individual among a larger group. I think that’s something people forget – they think “gosh, it’s too much, there’s no impact I can have”, but you can have. And it’s not just an impact for the environment, or society, it’s an impact for you. You can be personally empowered. You can be fulfilled. You can have huge reward as you work with others, share with your family – this is probably the most meaningful thing of all – is your own inner light.

This Sustainable Lens is from a series of conversations at University California Irvine. Sam’s visit was supported by the Newkirk Center for Science and Society, and coincided with Limits 2015.