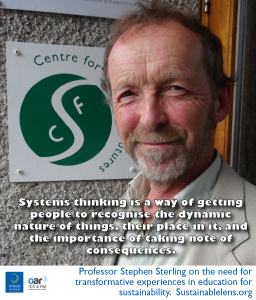

Professor Stephen Sterling is of Head of Education for Sustainable Development at the University of Plymouth. His argument that education needs to both transform and be transformative has transformed Education for Sustainability, both in the UK and internationally.

Talking points

I was an environmentalist before the term was coined

I read a book Teaching for Survival, about the time of the first big environmental conference in Sweden… and I thought, I’m going to get into environmental education, because that’s what’s going to make the difference.

(When did it become sustainability as we know now?) There was sent discussion pre-1987 but the Brundtland report was the turning point…the debate shifted up a gear and sustainable development became part of the currency.

1992 was a key point with the two streams really coming together

(Masters programme developed by WWF) Originally called Masters in Environmental and Development Education, it brought together the two streams, later it changed its name to Education for Sustainability.

“What’s your definition of sustainability?” is not a sound bite kind of a question. I tend to get round it by saying it’s the sorts of approaches (to education and learning) that we need if we are to assure the future economically, socially, and environmentally.

I see sustainability as a set of system conditions…conditions that for all intents and purposes can last forever, whatever system you are talking about. Sustainable Development is a pathway towards those conditions, but it’s a dynamic state.

I remember Crispin Tickell…talking about those three dimensions…not just in terms of having the three dimensions – because people think if you’ve got the three that’s it – but in terms of “seeing them in terms of each other”.

I make the distinction between the weak and strong sustainability diagrams. I go for the strong sustainability diagram – a systems diagram with concentric circles – economy being a subset of society, society being a subset of environment. The Venn diagram is good as a teaching tool – asking what is right and wrong with it? – but in terms of representing reality we have to go with a strong systems diagram.

Recently I’ve been working on, if you’ve got the philosophical ideas, how do they apply in a practical setting. The application of the ideas and their implications…is a challenge…how to reorient (higher education) towards sustainability.

I think one of the key problems with our western psyche is a reductionist mindset

People think that’s something that geographers and scientist should do, but we put it into yet another box

Sustainability is not the key issue…the problem is unsustainability

The key issue is why is a lot of what we do unsustainable?

What informs worldviews and mindsets…what does the required change in mindset mean, and what is the role of education in getting us there?

Education itself is not necessarily a solution unless we look at the assumptions and paradigms that influence educational policy and practice.

How can we rethink educational paradigms, policy and practice so that it is more amenable…the challenge of unsustainability and the opportunities of sustainability?

We need transformation in learner and process

We need learning processes that go deeper than content…engagement of deeper parts of our beings…requirements for teaching contexts

Getting people to think about deeper questions, their own assumptions and social assumptions…that’s where reflexivity comes in, and you can’t achieve a level of reflexivity with learners unless you have teaching and learning situations that stimulate that kind of reflection.

Always it’s a matter of bringing in sideways views and surprises in teaching methodology. For people to think “oh, ok, well..” and starting thinking and questioning and making enquiries that they wouldn’t otherwise not have made.

A lot of it is focussing on issues that are not amenable to standard solutions, maybe present ethical dilemmas and so on. That demands a deeper level of reflection than simple factual stuff.

Different disciplines will have different content bases, but sustainability demands a deeper response, making connections which otherwise wouldn’t be made.

I’ve made a career of trying to encourage teachers and learners to think in more holistic ways.

(How much do you need to front-load with gloom?) Not an easy question to answer – differences of opinion. Reality or disempower? Tendency…is to front-load too much around big issues and trends.

I think we need a degree of realism…there’s enough research reports to refer to…but balance that content around all the considerable initiatives, positive, driving forward that sustainability is inspiring.

Relational thinking.

Adjectival education…all about trying to improve relationships with something – relationality. ‘Education for change’ movements are all about trying to change relationships for the better.

Gregory Bateson in 1972 said we are governed by epistemologies we know to be wrong – objectivism, materialism, reductionism, dualism and so on. These ideas are part of the western intellectual legacy. These ideas cut us off from each other and from the environment. What we need to do is what Peter Reason calls an extended epistemology: embracing the other. Our relationship with others, our relationship with the natural world, our relationship with animals, our relationship with future generations. That idea of relationality is key to sustainability. A lack of relationship – a lack of identification, a lack of empathy – at it’s heart underpins unsustainbility, because we’re left with individualism.

We live in a systematic world

Everything is highly interconnected, and that’s been exacerbated by the technological revolution and globalisation, we need modes of thinking that are adequate to that highly interconnected world. If we think in a reductionist and individualist way, also an aggressive and competitive way, that’s going to cause more harm than good.

We need to think in a way that we are more aware of systemic consequences because they happen anyway

We need to use everything we’ve got at our disposal, some people are dismissive of social marketing “that’s not proper education”, but we need to use everything we have, time is short, if you can give people financial incentives to ‘do the right thing’ then that’s a start, and they might go beyond that to ask why they are encouraged to do that.

There’s no single answer to any of this.

All the issues tend to be related, we can’t just tick off climate change and say ‘well that’s done’, it has huge links with other issues, that was pointed out by Club of Rome, 40 years ago. We need to see issues together. That aside, the issue that worries me that doesn’t get much attention which I think is addressing biodiversity.

People tend to think biodiversity is ‘just a few plants and animals, very nice but we can afford to lose a few’, but that’s the web of life that supports everything else.

Quite apart from the arguments for the intrinsic value of nature – they have a right to exist in their own right – that’s whole idea of ecosystems services. The functions the ecosphere performs are vital, if that breaks down you can forget economic growth.

Clearly putting everything in terms of what nature does for us is important, but it shouldn’t be the only reason we’re looking after nature – intrinsic values not instrumental values

The Future Fit thinking framework is a practical guide

Focus on problem solving worries me

We live in a culture…coming out of our scientific legacy…we tend to think if we can define a problem then there must be a solution.

Clearly a lot of problems are amenable to simple problem solving…but not all problems are, and sadly a lot of sustainability problems are not of that character – they are complex, wicked problems that are not amenable to simple problem solving.

Learners need to be given a range of problems, from simple problems right through to complex issues – and get them to think how they should be approached differently, and that gives them an intellectual toolkit – to recognise that there’s no single category called problems, and that there’s a whole spectrum of different problems of different nature that require different approaches

Wicked problems can be approached…we can take actions which have beneficial systemic consequences. But if you take ill-considered unwise actions you start having a number of negative consequences that you didn’t foresee.

Critical thinking, but then what? What is your response to that? If you manage to raise someone’s critical awareness about an issue, but then don’t offer them a way of taking that inquiry forward, allowing them any form of engagement – that’s a bit of a half step – leaving the inquiry half way through

(Motivation) From when I was a kid, I’ve felt part of the whole, I’ve been outward looking, been aware of others – nature, animals, people, people and my place in relation to them – I’ve always felt that way and wanting to make a change for better

(Activist?) In a kind of way, yes, but not in the way that term often implies. I can look back over the last 30 years and know that I’ve enabled quite a lot of change to happen. To that extent yes, but I’m not out on the streets with barricades.

(Challenges) I find myself in a fortunate and privileged position, I want to use it wisely and well because it’s a responsibility.

I don’t write a lot of academic journal papers because I don’t think they make much difference, I’m in this game to change thinking and action.

(Miracle) What’s been frustrating has been a lack of real understanding by government and senior civil servants…if governments really understood the depths of challenges we’re facing nationally and globally over the next 20-30 years, maybe they would be more supportive the changes in education that I’ve been advocating

The reason governments don’t respond is for one of two reasons, one is that they don’t understand it, the other is that they do understand it. Because if they do understand, it means a radical shift in policy…and they’re not necessarily up for that.

(What could we do to simplify sustainability narrative?) An extremely good question, we’re stuck in a semantic problem, for some people we need to get away from the sustainability narrative itself and put it in terms people can come to terms with on their own terms.

Systems thinking is a way of getting people to recognise the dynamic nature of things, and their place in it, and the importance of taking note of consequences.

(Advice) Get informed, and get involved. There’s so much people can do at any level. At lot of it is possibly difficult but it is in many ways exciting.

Note: this interview was recorded in the week of the Scottish Independence referendum in early September 2014.