My analogy is saying that you’re going to do something about the road toll, that you’re addressing road safety, and shifting the speed limit from 50 km/h to 690 km/h. And conning the country that this is a fresh start for fresh water. That’s wrong in so many ways, but this is the reality for freshwater management.

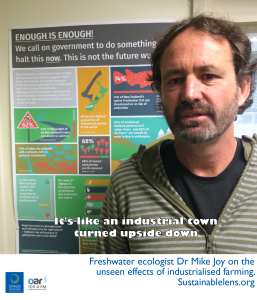

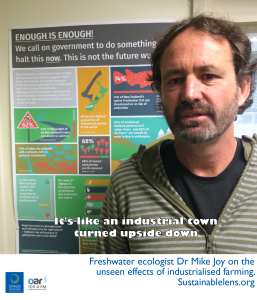

He wades in rivers so fish (and you) can swim in them. And he isn’t afraid to talk about who is to blame for what he finds there. Dr Mike Joy is a Senior Lecturer in Ecology in Massey University’s Institute of Agriculture and Environment.

Talking points

Our rivers are special – sadly really special now as we have the highest proportion of freshwater fish species of any country in the world.

More and more of our species are threatened species, yet we have this bizarre situation where they are threatened species but we commercially harvest them and we eat them. Most New Zealanders don’t realise that when you eat your whitebait fritter you’re eating threatened species. It kind of doesn’t fit with the New Zealand way. We get all upset with Japanese whalers and people shooting tigers, but for some reason – may be because we don’t know – we harvest and expert them, we sell our threatened species to other countries.

As indicators, fish integrate the health of the whole river, the whole ecosystem.

There are really clear patterns in relation to land use – intensively farmed areas, lowland rivers…really really bad.

The best habitats are the least available.

Because they are mostly migratory, most of the fish species are found closer to the sea, but that is the area where we have done most of the damage. Most of the conservation estate is unavailable to the fish.

We do have invasive species spreading through. In a pristine NZ river these invasive species wouldn’t do well at all, it is because we have changed our lakes and rivers to be much more like the kind of degraded, eutrophic, highly nutrient enriched habitats that these fish came from – we made it like that.

It’s a death by a 1000 cuts.

A combination of multiple impacts that accumulate down river. That’s the thing with rivers, all of the impacts just pile up – everything that happens on the land, eventually gravity takes it down to the river.

I used to have a chemistry lecturer that said “the solution to pollution is dilution”, but that is such an old dinosaur view of the world. Now that we dominate the planet we can see that dilution isn’t a reality – it doesn’t just go away, it accumulates somewhere. What I tell my students is “the solution to pollution is assimilation”. If the ecosystem can’t assimilate it, then you’ve got to stop putting it in.

Massive costs to engineer solutions to do what the river would have done for you if you hadn’t messed with it in the first place. It costs us so much more to do what nature would have done for us for nothing.

I realised that I was publishing well cited papers…but all I would end up doing is cataloguing the decline. I wasn’t just going to do that.

The only way to change is if public are aware of what is going on.

I use disaster (in the title of 2015 article “NZ Freshwater Disaster”) because if you look at the facts, there’s no way you could call it anything other than a disaster. If you look at the statistics then that’s quite moderate language, probably an understatement.

But at the same time as the public awareness is going up, we haven’t seen any improvement in the decisions that they’re making.

It’s getting worse, and we’ve had a big backdown on the protection as well. You can characterise what’s happening in freshwater as more and more money and more and more effort goes into public relations and communications staff – making things sound good. And hidden underneath all that is the reality that things are getting worse and the protections are being weakened.

People claim improvement (in the state of rivers), but that is wrong. There is no net improvement, there’s a couple of rivers that point-source discharges have come out of – pipes from meat works – improvement there but at the same time a net worsening.

Forget drinking water, most of our rivers you can’t drink, but even swimming – 62% of all of our rivers are unsafe to swim in.

The government response to that has been to shift from a Ministry of Health standard called “contact recreation”, that’s to protect you from getting sick if you get some water in your mouth, that’s 260 coliform units per litre of water. Now, it’s 1000, and they call it “wadeable”…you’re safe if you’re in a boat or have got waders on is the new norm.

They’ve shifted the goalposts to go from a map that’s mostly red to a map that’s mostly green. Shift the baseline…they did the same thing with nitrogen – from a protection of half a milligram of nitrogen per litre, and they’ve shifted it to 6.9mg/l. My analogy is saying that you’re going to do something about the road toll, that you’re addressing road safety, and shifting the speed limit from 50 km/h to 690 km/h. And conning the country that this is a fresh start for fresh water. That’s wrong in so many ways, but this is the reality for freshwater management.

Almost every industry, if it had to cover the true cost of clean up, it would be more than it purports to make. We’ve covered that up for generations, but it’s all coming home now because we are paying the price.

Dairy is the major driver on the health of the waterways.

It is so dependent on external inputs.

Just think about how unsustainable it is to make make milk out fossil fuels.

Planetary Boundaries – at a global level the planetary boundaries are exceeded seven fold when it comes to global nitrogen use.

We’re all part of that sad unfortunate sad reality that we’re feeding this massive population by using energy that was stored over the millennia. We’re living way past what the earth can handle.

Just counting the dairy cows, we’ve got a population of 90 million people equivalents. This puts it into balance, sure there are impacts of cities and so on, but it is tiny compared to just the dairy cows.

It’s like an industrial town turned upside down. Imagine Victorian England – all those chimneys pumping out smoke and the issues that came from that – flip that upside down, it’s the nutrients that leak out of the bottom of our farms through the soil that are the problems, but we don’t see them. If it were smoke coming over us we would all be so aware of it, but because it just goes down and through our waters we don’t see it.

It shocked me, waking up to hear John Key on National Radio saying that swimming in our rivers is aspirational. If someone says something that we take for granted and think part of being a New Zealander is suddenly aspirational , then where will we go next? Breathing without a respirator be aspirational? It’s a slippery slope.

Farms could make more money with half the cows, for a third of the pollution.

From an individual farmer’s profit point of view, they are losing money through overstocking. But they’re being driven by the industry to maximise production, not maximise profit.

You can see the limits of biological system, that production have gone up but profits haven’t.

There is a huge cost being paid here, but it is being paid by someone else.

What we are doing now is not conventional, it is very unconventional industrialised farming. Sustainable farming…backing off from the intensity, thinking about soil health, animal health, pasture health…biological farming, and the profits are much much higher.

Commodity market…the competition globally to make the cheapest product…the competition to have the weakest labour laws, the weakest environmental laws…we don’t want to win that race.

We need to maximise value by ensuring that people pay a premium for high quality food that is sustainably farmed. In the longer term animals have to come out of the human food chain.

A government that wanted to make a change would have to price externalities. We talk about this market economy, we supposedly have a market economy, so if we want a market economy the costs have to be borne by the people and organisations who are making the impacts.

(Success) I’m excited about Landcorp’s Environmental Reference Group. Industry has to lead the way.

(Motivation) A sense of injustice and anger.

(Activist) Yes I am, I give the Alice Walker quote at the end of my talks – that’s the price we all pay for living on the planet is to be active. We can’t sit back any more. If we sit back and think someone else is going to fix it for us, then we’re doomed. We have to all become active to change this. There’s some pretty big powers that are doing very well out of this and its hard work to take them on, so we all have to be active to do that.

As an academic it is part of my job. I have a role under the Education Act to be a “critic and conscience of society”.

(Alan Mark describes lobbying to remove him as an academic). I do know from the Vice Chancellor that Federated Farmers have regularly called for me to be sacked. But I’m still here. It is crucial for society that we have the ability to speak out.

(Challenge) Trying to get change, trying to show the way.

We get portrayed as a Luddite “you want us to go backwards”. But the reality is a sustainable world would be so much more fun, so much more exciting than a dirty world.

(Miracle) A government that actually had legislation for the people not for a few. And that would mean prioritising environmental protection over the profits of a few.

(Advice) The most effect you could have as an individual is to try and take animal agriculture out of your diet. But that is not enough, you have to be active, you have to stand up for your future and your children’s future, which means stopping the destruction.

Note. This interview was recorded just before the release of the NZ State of the Environment Report. Mike’s comments on that report, along with other leading scientists, can be found here.