Zak Rudin was one of the co-organisers of the Dunedin School Strike for Climate. Now he has finished school, we talk about what drives him and what’s next.

Zak Rudin was one of the co-organisers of the Dunedin School Strike for Climate. Now he has finished school, we talk about what drives him and what’s next.

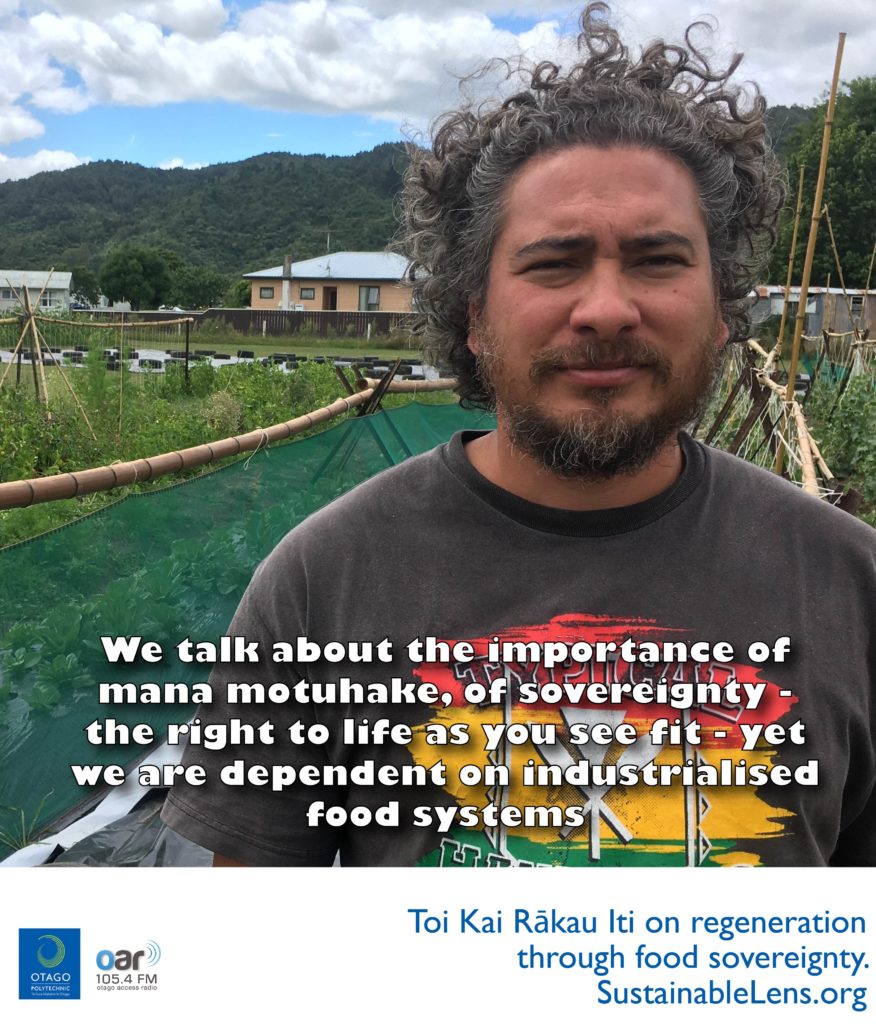

Toi Kai RÄkau Iti is of TÅ«hoe, Waikato and Te Arawa decent. An actor and documentary maker, he is back home in TÅ«hoe working with his community, HÄpu and Iwi. We talk about food sovereignty – agroecological regenerative systems which intersect western horticultural science with traditional TÅ«hoe ecological knowledge and practice.

Transitioning to a place of wellbeing

Te Reo – the magic of nature, codified in language

We talk about the importance of mana motuhake, of sovereignty – the right to life as you see fit – yet we are dependent on industrialised food systems

I come from a tradition of exposing the theatre of power, recoginising the power of spectacle, now we are developing a theatre of community

Food sovereignty is climate change

Gardening as performance art – this is a show garden, a manifestation of energy.

We see intergenerational dysfunction, we say karakia to the land, but then sit down to industrialised sausages.

The layers of colonisation are subtle, deep and thick.

In growing stuff – not just food – you can see the energy

Definition: It goes on

Success: Moving home

Superhero: Bringing value

Activist: Yes. Do stuff. Subversive

Motivation: Doing stuff for people

Challenge: Creating space for healing

Miracle: An awakening.

John Stansfield teaches Community Practice at Unitec in Auckland where they teach both undergraduate and post-graduate programmes in community development as well as social work and counselling.  He’s worked extensively in community development in his own community – notably Waiheke Island – as well as Palmerston North, Papua New Guinea and other Pacific islands.  He is chairing the upcoming Aotearoa Community Development conference.

| Â Shane | Welcome to the show John.

|

| John: | Thank you very much, gentlemen.

|

| Shane: | What we normally do is start off with a little bit about your past. Where were you born John?

|

| John: | I was born at a tragically early age in Auckland and I grew up initially in Te Atatu which is a glorious suburb on the harbour, in the upper harbour. I went to school there and lived there until I was about a teen or so when my parents had some kind of crazy idea and moved just to the Bible belt of Mount Roskill which amongst the many facilities it didn’t have, it didn’t even have a pub. I became bored with it quite quickly and at 18 I decamped and went and lived in the bush in Papua New Guinea for eighteen or twenty months or so.

|

| As far as growing up I’m still doing it. It’s been a long and difficult childhood.

|

|

| Sam: | What did you want to be when you grew up?

|

| John: | Goodness. Retired.

|

| Shane: | You went to Papua New Guinea and then you came back to New Zealand obviously at some point. What brought you back and what did you learn in Papua New Guinea?

|

| John: | Papua New Guinea was a transformative experience. I went there in 1976. It was a newly independent country. In fact tried to go in 1975 just as it became independent but they didn’t have embassies, you couldn’t get visas and it was terribly difficult. I got there and I worked as a motor mechanic in training, people in small engines in the bush in what’s now called Sandaun Province which was then the West Sepik as a volunteer and lived very simply in villages. Met all kinds of fabulous, fabulous characters. The ‘land of the unexpected’ as they call Papua New Guinea has a way of seeping into you and calling you back. I think I’ve been back more than twenty times since I left. I was fortunate enough, in fact, to go back and do some teaching up there, then later to go back and do some work for Oxfam. It’s a fabulous, fabulous country.

|

| Shane: | What first got you interested in going to Papua New Guinea? That’s not a standard path. Most people when they’re 18 head off to Europe or America. Why PNG and-

|

| John: | Well, in common with most 18 year old males it was not a rational decision. I think it was something which came about as an argument in a pub about whether I should join this movement to not have beer and pies on a Friday and put the money into aid and development, and being fond of beer and pies as my girth will tell you, I had to argue against it all. Actually I argue against just about anything, and said I’d far rather do something more practical with my skills and somebody called my bluff and said, “Actually there’s this unpaid job in the bush in the mosquito infested hell hole.” The West Sepik has the best mosquitoes in the world. They need clearance from civil aviation to land. They frequently make off with calves and small children.

|

| My bluff was called and I couldn’t back out and I went.

|

|

| Shane: | That must have been an amazing experience. Obviously you’re extremely fond of the country and the people. You came back to New Zealand what was your plan when you came back? Did you have a plan?

|

| John: | Sitting around in the bush with not too much to do but chew beetle nut and occasionally get a bit of wireless you get a bit of time to think and I decided that I really wanted to come back and study social work, but particularly what I thought was community social work which turned out to be community development. Just to add familiar with the term, I think of it as community development is the crucible of democracy. It’s the place where citizens come together to share their dreams and plan their common futures. It’s a way of collectively organising to make life better and that became my discipline and I’ve kept it for the rest of my life, and something I’m enormously fond of and very proud of and which defines me. These days I’m a senior lecturer community development, having become too old for useful work, I’ve returned to academia where it’s not object to advancement. I’m on the Board of the International Association of Community Development, and I’m chairing the Aotearoa Association and chairing the National Conference, and I’ve been fortunate enough to go on tour in March last year through India with twenty other community development practitioners. It’s fabulous. It’s better than religion.

|

| Shane: | Community development obviously is different depending what communities you’re in. The community in Papua New Guinea might be different to what community here or in Ireland or in India. What are the common themes and what are the differences and what do you have to be careful of going in…?

|

| John: | The great trap in community development is you really can’t have much of an agenda of your own. You have to help people find the agenda that they want. To give you an example, I chair a fabulous little organisation called the Waiheke Resources Trust. It does all kinds of fabulous projects in community development. We got a little grant here at council to see whether we could do something about food waste. Almost all the work that’s done on food waste is done after you’ve wasted the food. It’s a deeply stupid place to intervene in a problem. Myself and a young colleague intern wrote a paper doing a Lit review from around the world on food waste and said, “You got to start somewhere else”. Â We put this thing through to the Ministry for the Environment and they were pretty excited about it. Then they had a change of leadership and no one was really excited again. Â We pitched away and did a little trial at home. Ultimately we got the local council to say, “We’ll put some money behind you. Go and see what you can do.” They sent us off to a fabulous community we chose on Waiheke called Blackpool. Blackpool has a resident’s association which exists under the name BRA. The Blackpool Residents Association that came together when the community was flooded some years earlier. It had been little bit in abeyance. |

|

|

|

| We got that community together and we said, “Let’s spend an afternoon dreaming about what we’d really like in this community.” I kept in the background that we had a couple of young women, one of whom was working for us and one of whom was working for council in facilitating this process. “That’s good, we’ve got all your ideas, we’re going to write them up, we’re going to bring you back and John will cook you a lovely three course dinner with wine and candles and everything, then we’ll narrow it down and we’ll come up with what we’re going to do.” What we were wanting to do was inject some enthusiasm around sustainability and food waste. What the residents came up with is that they really wanted a pub. I thought fantastic, I can go back to the council and say, “Mr. Mayor, thanks very much for your money. Got nowhere on the sustainability, but the residents would like a pub, preferably on your land.”

|

|

| This could be the severely career limiting approach but actually we worked with that community and they got a pub, it’s a fantastic thing. It’s called the Dog and Pony and it pops up. It’s a pop-up pub, it pops up in a public building every few weeks and people bring their biscuits and their nibbles and their bottle of wine or their homemade beer and their violin and they have a fabulous time in their own community and they walk to it, walk home. No one gets killed in the process. The purpose of that story is to illustrate how it’s actually got to be the community’s decision what they want. Having got there and had the pub delivered, we were able to see who leaders were in that community and get alongside them and say, “Can we do something around food waste?” We did a fantastic trial there and really significantly reduced the waste of food and learned a whole lot that we’re now rolling out in other communities.

|

|

| Sam: | Is that easier or harder on an island?

|

| John: | It’s much easier on an island. Everything’s easier on an island. Not everything, you would run out of water here, that’s not easier. Your relationships are far more intimate. Everybody’s recycled. You have to be a little bit more both self-reliant and collectively reliant on each other to make things work. There’s an opening. I think on this island it’s a very proud history of concern about the environment and of being unafraid to stand up and be counted on things. We were the first place in New Zealand to be nuclear free. I think we were the first council to declare ourselves GE free. When the boats left for Moruroa, they largely came from Waiheke. We’re a great bunch. It’s very easy to find other people of like mind in this community to do something that’s better for everyone.

|

| Sam: | Then you have a council that is representing all of Auckland and does things like destroy your waste management system.

|

| John: | You’ve got to have the time sense of a geologist to appreciate these things you see. We originally had a couple of roads boards here, that then got made into the Waiheke County Council. I remember the Waiheke County Council very fondly. A place where politics became a blood sport and source of local entertainment where people jostled to get a seat at the local council meeting, try deftly to be upwind of Fred Burrock who hadn’t washed. We were one fantastic county. We did things like say, “It’s our island and we’re going to green it.” They built their own nursery, employed four or five islanders and every ratepayer could front up and get three trees any time he liked. They get your fruit trees and fruit trees were planted on the road verges, in public parks and all over the place.

|

| That was fabulous. Then it was compulsory amalgamated with Auckland City Council which is no longer. Waiheke revolted of course because the first thing that the good burghers of Rocky Bay knew about the amalgamation is they came down their muddy track with the carefully sorted recycling was a big flash new council truck going past and threw the whole lot into a compactor and took it off to a hole in the ground. We were pretty vexed and aggrieved about that.

|

|

| When the Royal Commission on the Governance of Auckland asked the then 1.4 million people of the region to comment on their plan, 28.8% of all submissions came from the 0.8% of the people who lived on Waiheke who demanded that the commission come here and explain themselves about how we were going to do without local governance. Ourselves and the Great Barrier community won their own local governments back. Yes, it’s true that we did lose the fabulous social enterprise in rubbish but we’ll win it back. We [inaudible 00:12:46], we can write.

|

|

| Shane: | It sounds like there was already a community there to work with. How do you development a community where the one doesn’t already exist or it’s very fragile?

|

| John: | There’s been some great work done around that in New Zealand and overseas. In fact, I had a cup of tea this morning with my very good friend, Gavin Rooney who at 76 has just retired from being a senior lecturer in Community Development. He was the first local authority community worker employed in New Zealand. They put him in the new Nappy Alley suburbs of Massey out in West Auckland. When he finished his term, they didn’t appoint a new one, the council, because they had so much trouble with the last one. He just very patiently went around, getting to know people, linking people up. Getting conversations going about things. Similarly a great New Zealand community worker was Wendy Craig who worked in the Takaro community of Palmerston North. Was very famous there when the hospital board were considering closing a maternity unit. Wendy got a whole bunch of mothers with crying babies to go to the hospital board meeting. I think it was a bit of judicious bottom pinching during the meeting because the meeting had to be abandoned there was so many crying babies. The board got the message, they shouldn’t mess with the women of Takaro.

|

| It’s a gentle process of getting to know people, finding their interests, linking them up with each other. Making it possible for people to believe that they can control their own futures and have a say. Once you get to that point it’s pretty unstoppable.

|

|

| Sam: | We visited Oamaru last year, or the year before, they have got a really strong transition town movement. They’ve got a really good summer school and they’ve got their, what do they call it…The waste recycling system, they’re planting trees on every street frontage. Whole pile of things. We thought, “This is amazing. We have to go and find out they’re managing this. How is the whole town in behind transitional Oamaru?” It turns out it’s not. There’s about six people doing everything but what they’re doing is doing things that other people would get engaged in. Even if they think the transitional town people are a bit weird, they still recognise that having fruit trees in front of their house is a good thing.

|

| John: | Transition towns, it’s somewhat kind of like a brand really. They came to Waiheke and the next thing we noticed was all kinds of things we’d already been doing with transition town things. That’s good. They’re able to reach a different constituency. Every little tribe that marches in a similar direction that reaches a new constituency makes us all collectively stronger. It’s great.

|

| Kaikoura is another place that’s fabulous. Kaikoura, when I was down there last week helping sort the rubbish on the line in the recycling plant because her brother, Robbie Roach, is the manager of Innovative Waste Kaikoura. He is facing a mountain of construction and demolition waste and working out has a community they can make the best of that. Wonderful. There is actually a lot of be said for rubbish. I started to think that we’ve got to grab hold of all the rubbish and keep it for the poor before the rich find out how bloody valuable it is.

|

|

| Sam: | One time I visited Waiheke and the rubbish was sitting in some sort of carton or big crate thing on the wharf. I thought, “All the people that go over the wharf can see this is the result of our through-put.” It’s nice and visible. You don’t need to have a website or anything. Unfortunately that’s gone. My question though, was is there a tipping point of how much community engagement you need to actually make a difference?

|

| John: | If I refer back to my good friend Wendy Craig, who’s a very wise woman. She said once, “If you’re fun to be with, they’ll always be people with you.” Two essential ingredients for good community development are fun, coupled with a deep seed irreverence, and food. If you put those two things together you can find ways to build bridges and get people engaged. Once people become engaged in their own neighbourhood and there’s oodles of research out that says people want to be more engaged and they want to do that locally. Somewhere where they live. We just seem to have built a social structure that’s going entirely in the wrong direction for that. Some clever marketing guru gets hold it, they’ll be community development on sale.

|

| I suppose there is a kind of tipping point but it’s a tipping point. It just takes a little bit of enthusiasm in pulling people together and it has its successes and its failures. It requires some judicious thinking about what would be good early successes because nothing succeeds like success. People’s experience of a win is very empowering.

|

|

| Sam: | You’ve written about foreign issues. You write about gambling and the relationship between gambling and public health. What’s the cross over between that and the collective organising and community development we’ve been talking about?

|

| John: | Sure. This second stint in academia. I was here in the mid-90s and I founded a graduate programme in not-for-profit management. I started to wonder, I actually wondered this on a beach with a great American guy called Tim McMain. We sat on a beach and wondered this together whether the biggest threat to biodiversity was not the loss of Hochstetter’s Frog, or the Maui dolphin, but the most important biodiversity was the biodiversity of thought. What I observed happening around the world in terms of governance and management was that there was starting to be a one true solution, one size fits all. Funnily enough it happened to be the one that culturally suited white men in suits from Boston. You saw other ways of doing and knowing and thinking being pushed out to the margins. When I looked at the impact of that on the community sector I became deeply concerned at the kind of corporatization that was happening all over the place that was actually driving out the most important thing we do in the community organisation which is giving people the opportunity to belong. Belonging is just really important for people and for healthy societies. If you don’t think it’s important, go to court on a Monday morning. You’re not going to find many playcentre mums.

|

| We started to think about this thing about actually the way we manage community organisations has to palpably different, it has to have its own kaupapa, it has to have its own culture. It has to have a consistency, because you don’t have the same tools. You don’t have the same money that you can incentivize and you don’t have the legislative power of the state. All you have is trying to get people to line up around some values.

|

|

| I did that for nine years and then I did a dangerous thing – I had a holiday. I woke up from that I thought, “I wonder if I’ll still be here, preaching on like this in thirty years time. I should go and find out if it works.” I looked for a broken community organisation which was the Problem Gambling Foundation. I was fortunate enough to be appointed their CEO, and I had a really fantastic five years. Learning about gambling and its impact. My thinking is very influenced by the late, great Bill Mollison who developed Permaculture. I’m sure some of your listeners will know about Bill and he and David Holmgrem’s work.

|

|

| When I got to the Problem Gambling Foundation, things were quite broken so I couldn’t hop into the track and blast off into the sunset. None of the gears worked, the wiring was buggered, and the finance system didn’t work. It was just a bloody mess. It was a lot of grunt work to be done for about three months. While I was doing that I decided I’d have a Masters level education in gambling. Every night I would read two or three hours worth of papers from around the world about gambling. What I quickly found out is that more than half of them had all the validity of 1950s tobacco research, and for exactly the same reason. Just as the tobacco companies corrupted the research sector by buying it, so had the gambling industry. That really made it hard. I didn’t know. I didn’t know what the answer was. I had to keep looking, keep looking, keep looking. One night about 10:00 I came across one statistic and it showed me that ten years earlier, no New Zealand women had come to treatment for gambling problems. Yet, now in 2003 this was, more than half the people coming were women.

|

|

| If you approach that bit of statistic with the traditional addictions lens, and addictions looks at the person who is harmed after the harm has happened and says, “What is the matter with the person?” Then the question you ask is what happened to New Zealand women that they all got so weak over ten years? Mine has not been a life which has been surrounded by weak New Zealand women. I tend to end up with the very mouthy, stroppy ones. There’s still time. It’s a species I’m interested I’m explore. I thought, “This just doesn’t make bloody sense.” I fell back on my trade union background, I thought, “If I’d gone to a mill and there were three blokes sitting around with their arms cut off, my first thing wouldn’t be to get them into a support group and say, “now come on you fellas, what happened in your earlier lives that caused you to cut your arms off?” Essentially that’s what we were doing with gamblers. We were getting people who would come in who were deeply harmed and saying, “This is your fault in some way.” It isn’t.

|

|

| The normal outcome of regular use of a pokie machine is that you’ll be harmed by it. It’s a deeply, deeply pernicious industry and it extracts money out of the communities that can least afford it. You follow the capital flows? It’s a transfer of wealth from the women to the men, from the brown to the white and from the poor to the rich. Once I understood that, I knew that it was deeply offensive and I could have a great deal of fun fighting it. It’s just like any other kind of plunder, environmental plunder or community plunder.

|

|

| Shane: | Why has New Zealand’s society allowed that or constructed a system? This kind of gambling, for instance, isn’t simply legal back in Ireland and I was really shocked when I came over here to see the pokie machines and the casinos. What allowed that? What was the construct there?

|

| John: | I’ve always wondered if in Ireland the reason it didn’t go ahead was because the church couldn’t find a way to control it. Just as an aside.  The way gambling gets in everywhere is a bit of a standard method and it’s lies, deception and corruption. They have fantastic relationships with senior people in government. I can think of a fellow in a one man party, and I don’t mean David Seymour, who in his entire career in politics has never voted against the gambling industry, the liquor industry or the tobacco industry. He stands for Family First party. Think about that.

|

| They use all kinds of chicanery in communities and they have got oodles and oodles of money. I often used to say, “Any idiot could run a pokie trust and usually does.”

|

|

| Sam: | What do you do about trying to change that behaviour if you’re taking that collective responsibility role that you’re talking about. The point is that it’s already normalised.

|

| John: | People aren’t stupid. In fact what you see happening with the pokie industry up until the last two quarters is a poisoning of the well. There’s very few people in this country now who don’t know somebody or some family that’s been blighted by those machines. It’s really, really hard to walk into anywhere they are and imagine that there’s something glamorous going on. All you really have to do to fight against this is number one, tell the truth, and we tell the truth about it on a daily basis through a news feed called Today’s Stories that a wonderful woman named Donna in Auckland puts together every morning. Gets on my desk about 7 a.m. and it’s a summary of all the gambling stories in New Zealand and around the world.

|

| You find things like the second biggest motivator for organised fraud, white collar crime, and this is a top accounting firm study, is gambling. Unless you look at the charitable sector alone in which case it’s always the highest motivator. Gambling is only allowed in our society really for charitable purposes but the people most likely get harmed by the charities. When you start to tell that story repeatedly it starts to become true. The latest surveys by the Department of Internal Affairs now show that the majority of New Zealanders don’t think it’s a good idea to fund communities out of the gambling industry. While the minister, Minister Dunne, is desperately trying to liberalise the regime and ensure that pokie machines are a sustainable industry. You can’t put glitter on a turd. It just isn’t going to work. Ultimately, people will throw them out and I think we will look back on this period of our history with a sense of deep shame and say, “How did we allow that level of exploitation of our poorest and most vulnerable citizens.” Make no mistake it’s the poor who pay the price of pokie gambling.

|

|

| I put a picket on a pub in Manurewa years ago and they have 5.1 million dollars from that poor, poor, poor South Auckland suburb leave town. Some of the money went to charity, it went to the Otago Rugby Union, and the Canterbury Jockey Club. The horse owners which apparently is a sport. Not one red cent went back into that community yet there were moms dropping the kids off at school in their dressing gowns coming into that pub playing those machines. Desperate to try and win some of it back.

|

|

| Sam: | Talking about stories and telling the truth, I’m thinking about now as we move very quickly into what’s being referred to as post-truth, or whatever. We’ve been having the same thing on a lesser level for quite a long time here about the story, it’s all right Jack, everything’s wonderful on Planet Key. Is that making it harder to engage communities because they’re being told so strongly that everything’s all right?

|

| John: | Yeah. There’s certainly something very comforting about the news according to Mike Hoskins. It doesn’t really bear looking at. Put it in context to the States, I was in the States during the period of the conventions. I just couldn’t believe it. Come on, you people, you’re not stupid are you? What’s going on? You wonder how long it would be before particularly working class middle America wakes up and realises they’re seriously being duped. There is I think a real risk in our society in the decline in journalism. I don’t mean that journalists are any less than there ever were, great journalists in this country but there’s a hell of a lot less of them. They’ve got a hell of a lot less time to do their job. There’s a lot of stuff that’s just sliding by. I just about fell off the chair when I read that we were the least corrupt country in the world.

|

| Sam: | You’ve written about gagging, I think in relation to Christchurch. Do you think we’ve got a problem with people in government, local government, national government, being told what they can and can’t say?

|

| John: | Yes we have. It gets passed down so that one of the real roles of the community sector, and community development organisations is to get people together and speak on their behalf. What we’ve seen with the rise of contractaulism and the relationship between government and the community sector is that those contracts are used to exercise gagging and changes in governance and all manner of restrictions. I remember at the Problem Gambling Foundation getting told that we provide free counselling services in prison. That we would not be able to have a contract if we continued to provide free counselling services in prison. Their organisation was actually born in prison. A couple of guys realised they were in prison because they gambled, they decided they were going to do something about it. We had very deep roots to that. I said to the officials at the time, “Hell will freeze over guys. Let’s see who’s going to blink first.”

|

| We were a long time, many, many, many months with no income. Staring down the barrel of that thing. You can’t withhold medical treatment, which is what counselling services, from people in prison. That’s in breach of international human rights codes. We won’t participate with it. Boy, did that organisation get punished by the Ministry of Health for having an ethical position. They certainly did. They still got that ethical position I’m proud to say.

|

|

| Shane: | Do other organisations look at that example and then think we’d better not cross government?

|

| John: | Yeah. Absolutely. A terribly expensive case for an organisation to have to take. All brilliant work that was done by a fantastic team of lawyers but by golly it doesn’t come cheap. Just to preserve what you already had.

|

| Shane: | What we’re saying is what we’re seeing happening in America in a radical and very clear way, has been happening slowly here for a long time?

|

| John: | Yes, I do think some of that but I also think that we owe it to our communities not to be timid and not to self-censor. I can put up with being censored by the state, I can rebel against it, I can speak out against it, but I’m far more worried about people doing the Nervous Nellie and self-censoring to please.

|

| Sam: | You’re Head of Department of Social Practise-

|

| John: | I was Head of Department, I’m happily now … Poor Robert Ford has that honour. I’m now Senior Lecturer in Community Development.

|

| Sam: | Okay. You’re teaching people how to be community development practitioners.

|

| John: | Yes.

|

| Sam: | Are you training them to be trouble makers?

|

| John: | Absolutely. Definitely. We’re training them to be true, to look at injustice and impoverishment and know where they’re going to stand. Really they are the most delightful students. It must of been 2015 I think, I had a student come into my office breathlessly and say, “I did something!” I said, “That’s good, we’ve all done something. What is it you’ve done?” “I can’t even tell you.” She passed me a phone and she set up a Facebook page to plan a protest on TV 3 about the proposed closure of Campbell Live. I said, “That’s fantastic. Terrific! We’ll talk with the class about it.” She said, “I’ve never been to a protest before!” “Oh well, that’s fine. We’ll have a look on the computer, we’ll find you one to go to.”

|

| Her group of them went off down and helped the McDonald’s workers fight the good fight against zero hours contracts. Then they lead a protest march to TV 3 and they got inside and occupied the building and had a wonderful time. Sat on the floor and slapped their thighs and said, “This is what democracy looks like,” and I was terribly, terribly proud of them because that’s how you build a people who will not be bowed. The risk that we have all around the world at the moment is that government’s lose the understanding that they government by consent and that that consent can be withdrawn.

|

|

| Sam: | Those young graduates of yours, the ones you’ve trained to be trouble makers, they have to go into organisations that rely on government funding.

|

| John: | They do.

|

| Sam: | How are they going to manage that tension?

|

| John: | Life’s full of difficulties. I talked to one just the other day who did a TV show by posing as school children buying single cigarettes. She’s happily found work in a tobacco control agency. I think young people are actually pretty smart. What I observe happening around the place is some very good advocacy training is going on. I went out on Saturday night and I met Sandy, the producer of the documentary Beautiful Democracy which is about the young people who lead the TPPA protests. Gosh, my heart was so warmed by the fact that these young people were really deeply thinking about their tactics, what would work and trying things out. Doing fantastic research. Really deeply engaging in this society because engaged citizens aren’t the ones you’ve got to fear. It’s the ones who aren’t engaged you’ve got to be worried about.

|

| Sam: | You are chairing, I think, the Community Development Association conference coming up-

|

| John: | I am. yes, it’s a fantastic honour. I’m thrilled to bits.

|

| Sam: | What sort of things can we expect? I should say I’m going to it.

|

| John: | It’s going to be fantastic, really is. We’ve got, as of this afternoon, 170-odd people from around the world coming. What we’re doing is we’re using a community development lens for by and large people are community activists, community development practitioners and academics and leaders. We’re using that to look at the United Nations have deemed Agenda 2030. Which is the goal of sustainable development. Ordinarily if you wanted to talk about the United Nations, you put me into a deep sleep instantly. The seventeen goals for sustainable development are a fifteen year plan for the whole world, and they are just about the most important things we could be dealing with. It’s ending poverty, it’s ending hunger. It’s about having gender equality, it’s about having good health care. It’s about having good education, and other things that you wouldn’t expect. Like access to clean and affordable energy.

|

| One of the guests who’s coming in is Kalyan Paul who’s from Pan Himalayan Grassroots Development Foundation and is from Ranikhet in the Almora District, Uttarakhand in the foothills of the Himalayas. I went up and visited him and he works with the forest dwellers and the people who live in the deep, deep valleys. We were talking about Agenda 2030 which brings together a lot of social goals with a lot of environmental goals. He said to me, “Look, it was inevitable. This is completely inevitable. We’ve known this would happen.” Where did he bloody know that sitting up here? He said, “You can’t protect the forest if the people have no fuel for their cooking. You simply can’t do it.” The only way we’ve managed to protect all this beautiful forest is by addressing the problem, and that is they built small biogas plants. They take the cow dung and human dung and produce gas which does the cooking and lighting. The houses don’t need to walk miles into the forest and cut the trees down. Then you can protect the forest.

|

|

| Very practical solutions but based on some really good deep thinking. This wonderful confluence of the social and the economic and the environmental. It’s a really exciting time because many people in community development actually have got a huge contribution to make to the way we take this stuff forward. Companies are looking at this stuff. One of the big multi-nationals, I can’t remember exactly the name. They probably made your toothpaste and soap this morning. They have so many tens of thousands that they give out in grants and they have so many thousand days a year of corporate volunteering. They just announced Agenda 2030, as of June all about volunteering, all about donations and everything, are going to be targeted on the seventeen sustainable development goals. All of our industries are going to be measured against their contributions to those goals. This is really big, big stuff.

|

|

| Sam: | All right. We’re running out of time and I’ve got seven questions to ask.

|

| John: | I’ll try to be brief.

|

| Sam: | We’re going to have to rattle through them. What is your go-to definition of sustainability?

|

| John: | Pass. I haven’t got a short one for that. The Brundtland Commission which is to consume today only so much as to ensure tomorrow can. Is still pretty good.

|

| Sam: | That’ll do. How would you describe your sustainable super power? What is it you’re bringing to the good fight?

|

| John: | A really good sense of fun, a deep reverence for food and a great love of people.

|

| Sam: | I think I know how you’re going to answer this next question. Do you consider yourself to be an activist?

|

| John: | Absolutely. Activism is the rent price that you pay for living on the planet.

|

| Sam: | Have you always thought that?

|

| John: | Pretty much I think. My mom would say so. She said I was this troublesome in primary school.

|

| Sam: | Have you ever been a position where you couldn’t be?

|

| John: | I’ve often been in a position where I couldn’t be as activist as I might like to be. I know some fabulous people and I was reflecting with Gavin this morning on an experience I had in a government committee meeting where I felt that the principle that was being applied was deeply, ethically wrong. The others stood with me, he lost it as a vote but when I put it out, impassioned it out, others stood with me. You go, okay, I just didn’t win it today. I’ve got to come back and be better next time.

|

| Sam: | You said something that was deeply ethically wrong.

|

| John: | Yeah.

|

| Sam: | Where did those ethics come from?

|

| John: | Gosh. I think you get a lot of them from your mom. I know I get my sense of fairness from my mom. She’s still alive, she’s pretty smart. She knows that if she cut an apple, I’d want to have the biggest bit and my little brother get the smallest bit. She’d do the Solomon trick, she’d say, “You cut and he chooses.” Never seen the precision going into cutting an apple like that.

|

| Sam: | Do you think that people like coming through school getting that stuff?

|

| John: | You have your moments of despair about it. I have an absolutely 18 year daughter of whom I’m incredibly proud. She’s on every kind of activism there is. She is on so much more activism at 18 than I was that I feel very hopeful for the planet. Again, meeting Sandy on the weekend and looking at the film and the other film around indigenous housing and some of the young people coming through the programmes that were involved, I think there’s some pretty fabulous young people out there.

|

| Sam: | What’s your daughter going to do with that? There’s not many programmes like the one you teach where we’re actively teaching people or even allowing people to be activists.

|

| John: | She’s going off to Victoria University next year and I said, “Are you going to do politics?” She just looked at me, she said, “You don’t think I get enough politics at home?” She’s got a love of languages, she’s travelled, she’s Maori so she’s going to do some Maori studies and some law and some languages. Whatever she does and learn she’ll make a big difference with her life, I can just see it.

|

| Sam: | What motivates you? What gets you out of bed in the morning? A pretty stunning view I must say.

|

| John: | It is a stunning view. I leave it in the dark, can you believe it? I belt out of bed before 5, and I’m out of here by half past to go all the way to Henderson to do the job there. Lovely team of people that I work with. I think that most people want a job worth doing, they want a team worth belonging to and they want leadership worth following. Two out of three ain’t bad.

|

| Sam: | That’s quite a commute.

|

| John: | It is.

|

| Sam: | Ferry and then train?

|

| John: | It’s currently either car or bicycle to the ferry. Then ferry and then most of the time it’s taking the little campaign car that we have because it’s got to live in a concrete bunker. At that time of the morning I can be in my office by 7 which gives me clear, early part of the day. When the new trains come and we’ve got a route that doesn’t go by Kazakhstan that might be an option.

|

| Sam: | What challenges are you looking forward to in the next couple of years?

|

| John: | I’m really looking forward to the conference and that’s challenging on day by day basis. Got one of the young graduates managing that process. It’s just fantastic. A young woman that can take any pile of drivel that I put on the page and turn it into something that looks like a masterpiece, so that’s fabulous.

|

| After the conference I’m planning to do a major piece of research in New Zealand on the behaviour of funding organisations and the processes and how this does or does not contribute to innovative and sustainable funding relationships. I’m planning on doing that piece of work for a few years. I’m just finishing a piece of work on the living wage movement, and also helping on a project looking at South Kaipara community economic development scheme which is featuring in the conference. That is all pretty good.

|

|

| Sam: | You’re a busy chap, especially with the dancing in the garden stuff?

|

| John: | Dancing in the garden is a great deal of fun, yeah. They’re going to get a film maker there. He just as to look at me in a certain way and I can’t help myself. I become a total show-off really. The garden is very important to me. I have a great garden here, it’s still looking fabulous but we’re entering drought now so it’ll all be dead in a fortnight. Organic food, really, really important to me. Food’s really important. Sharing it with people.

|

| Sam: | Two more questions unless I get distracted.

|

| John: | Sure.

|

| Sam: | If you could wave a magic wand and have a miracle occur by tomorrow morning what would it be?

|

| John: | My standard reply to that is that every wish that would ever have would come true but I don’t think that’s going to wear in this occasion. Gosh. Would we have to fix the climate. That would have to be the top. The two problems we’re going to deal with are inequality and the climate. If we get those things stopped the rest of it’s a piece of cake.

|

| Sam: | What’s the smallest thing that we could do that would have the biggest impact on either or both of those?

|

| John: | I think if we all really looked at inequality in our society and started having a real discussion about it, and saying, “No, I don’t believe these Kiwis really want to have a third of children living in poverty.” That’s been able to perpetuate because we have not been having the conversation and we have to have that conversation really, really robustly.

|

| Sam: | Last question before we get in trouble with the Buddhists, do you have any advice for our listeners?

|

| John: | Live long, it’ll damn your enemies.

|

| Sam: | Great. You’re listening to Sustainable Lens on Talk Access Radio 105.4 FM. This show was recorded on the 26th of January, 2017. Our guest was John Stansfield

|

There’s always been this association of higher learning to progressive social movements…Instead of saying that this is something that happens on the fringe of university culture, why can’t we make this a learning experience?

Our guest tonight is Associate Professor Bob Huish from Dalhousie University. He’s part of the International Development Studies Department at Dalhousie, and a recipient of the 2015 Insight Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council in Canada.

His research explores ways in which social activism can lead to comprehensive development outcomes. He focuses on global health inequity and the role of activism in bringing about improved provision of healthcare and resource poor settings. Beyond community based health advocacy, he examines how medical education acts as a determinant of global health and equity, particularly with regards to Cuban Medical Internationalism.

It is well known that while many diseases favour the poor, the ability to treat and prevent illness tends to favour the affluent, and we’ll talk about that a little bit later. He pursues research about the pedagogies of activism and the organization of social resistance. He also explores the role of sport for development with special attention to Cuba and how this facilitates comprehensive development as well as organized forms of resistance.

At the moment, he’s currently working on following four areas, might be some more when he talks about it a little bit later on: Cuba sports internationalism solidarity, the pace of activism in the future of the university, global health assets, and human rights activism in North Korea.

He’s presenting a lecture entitled, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind, Out of Bounds.” Dark connections between offshore capital sanctions and human rights abuses in North Korea, which sounds very exciting there. It’s on the 14th of September at 1:00 PM, it’s in St David St lecture theatre. You also have one on Tuesday, which we just found out about before the lecture at 5:00 PM on Tuesday. I’m going to talk to you about that in a second.

You’re also currently the Ron Lister fellow in the Department of Geography, the University of Otago, which is why you’re here. Welcome to our show. Welcome to New Zealand.

Bob: Thank you very much. I’m delighted to be here and loving being in Dunedin.

Shane: This all sounds really fascinating, but tell us what the lecture you’re giving on Tuesday.

Bob: Tuesday is the Ron Lister Visiting Fellow lecture. That’ll be at 5:15 on the campus. I believe it will be in room … I’ll find it for you.

Shane: You find it and get back to us. (Burns 2)

Bob: Yes, I’ll get back to you on that. It’s going to be talking about some of the research I’m doing involving North Korean human rights. As geographers, as the department of geography, we are all about going to places, experiencing that place, learning about the land, the life, the interactions. What I’m talking about on Tuesday is as a geographer, how do you research a place that you cannot go to, that is totally forbidden.

To go to North Korea, if you were there as a tourist, you would spend about €4000 for a week there, and you’d be given this veneer tourism. If you were to go in there illegally, you would risk your life. It’s very hard to get to see the realities of a place like that. Yet we know that this is an area that requires both scholarly and moral attention. How do we address it? That’s what I’ll be talking about on Tuesday night.

Shane: That sounds really exciting. Before we get into that, this is just absolutely fascinating stuff for me here. These are really, really interesting topics. We’ll go back and we’ll talk about, you grew up in Canada, I take it?

Bob: I did, yes. Six generations, Canadian, both sides, mother side and the father side.

Shane: Where in Canada were you brought up?

Bob: I was brought up in a place called Wasaga Beach, Ontario. Wasaga Beach’s claim to fame is that it is the longest freshwater beach in the world.

Shane: Wow. Was that mean that you spend lots of summer evenings down on the beach?

Bob: Absolutely. It’s a place where you have 18 kilometers of pristine beach. It’s inimitable. Then a couple of areas of the beach, we would let the tourists come over and take over and destroy the place, but we would maintain at least a good 16 kilometers for local activities. Now it’s a provincial park that’s protected for environmental sustainability as well. Lovely spot.

Shane: Is this what got your interested in geography? What made you become a geographer? Was that something that happened in school, or is it just something?

Bob: It was. I grew up wanting to travel and explore and take photos along the way. I remember telling the guidance counselors at the high school that I was going to either be a pilot or a National Geographic photographer. To be a National Geographic photographer, good luck. All the best to those to do it, but it’s a very competitive field. I figured a pilot would be a good way to see the world. When I went in for my medical test at the age of 16, the physician who did the test, you go through a few things, gets onto the eyes and he takes out the colour blindness book, and I’m seeing numbers that he doesn’t.

I remember him laughing out loud about how hilarious this was. I just saw, at the moment, my entire career and future just fading away. I went and talked to a high school teacher, Dave Knox, who had a radio show himself, avid rock and roll fantastic, but also very dedicated geographer. He pointed me in the direction in geography. It’s a field that will, pardon the pun, but it’ll take you places. I’ve stuck with it ever since.

Shane: Brilliant.

Sam: Shane’s always incredulous that people want to be geographers. We of course understand why you’d want to be a geographer.

Shane: It’s just that in school, it’s taught in the most boring way. Once you get to university, it resembles nothing compared to what you did in school. I’m always fascinated by this, physics is natural continuation but … Did you get frustrated with how high school teaches geography?

Bob: At the time, I was fortunate to have some really good high school teachers. Dave Knox was one, this other guy, Wayne Hunwicks, he was a fantastic teacher. I was really fortunate to have that growing up. Now looking back, to look at what a lot of geography is presented, in Canadian high school, I can speak to specifically, there is a disconnect. I think that when students come into university and they have an idea of what geography is in terms of making maps and capitals and mountains and ice and whatever else, to see the rich context that geographers, researchers and university professors bring to the table, it can be a very uphill battle for students in the first year or so.

Then once you realize how appreciated geographic research is in other disciplines, it’s incredibly rewarding.

Shane: Yeah, you always just think it’s like what you learned in school….boring, but it’s not, it’s just absolutely fascinating and really … You examine so many different areas of life. Let’s rush on. You obviously got interested in health.

Bob: Yes.

Shane: How did you get interested in health?

Bob: It was when I started doing work in Cuba. My Master’s project involve trips to Cuba to do work there. It was more in a historical, cultural geography framework. When I was in Cuba on the first day of arriving, this would’ve been April 30th. Still a bit chilly in Canada. You have a group of Canadian students who are coming down to the Caribbean for the first time, and we are exposed to this beautiful Caribbean sea. The first thing you want to do is jump into it.

No matter what culture you’re in, what language you speak, a red flag on the beach means what?

Sam: Danger.

Bob: Stay out of the water. Next thing you know, I’m the first guy in. It was this wave that came up, crashed over me, over my head, took me down and did one of those things where you’re corkscrewing. Smash, right into the rocks. I had my shoulder hanging open. I remember crawling out with one hand out of the beach and these two guys come in and they say, “we’ve got to take you to the hospital, man.” I thought, “I don’t want to go to a Cuban hospital, this isn’t what I want. It’s okay, I’ll walk it off.” You look over and the shoulder’s gaping.

They put me in the back of a ’53 Oldsmobile, picked up another guy who’d cut his foot open on a beer bottle, and we went straight to the hospital. We were both stitched up, cleaned up and out the door in 20 minutes. The next day, a nurse actually came by the hotel and said, “Hey, how’s that guy with the shoulder?” This was a time when some of the most wealthy and affluent countries were exercising extreme austerity on their healthcare systems. To me, being in a resource poor country that has many democratic and social problems, to extend that healthcare to a foreigner for no cost really resonated. I wanted to know why that was.

From there, it opens up a whole new area about what is healthcare, why does place matter to it, what can we bring to learn more about how this experience can be repeated.

Shane: Do you ever reflect on that one moment possibly changed your whole direction of your career?

Bob: It definitely did. What I did was I went back and started to do research in Cuba for a few years. After that moment, I started to look more about the health indicators. You see that in almost every category, Cuba, whose economy is not that great, especially then, it was in line with Mozambique and Vanuatu in terms of economic growth, but its health indicators were outperforming most European countries, certainly outperforming the US and Canada in many regards.

When you start looking at the data about what their health indicators are, their capacity to train physicians and nurses, their approach to health, not as a product of a physician’s craft, but as being produced from issues of community sustainability, that opened up the whole gates. That’s what I’ve been doing ever since.

Shane: That’s quite a different fundamental point of view approach to healthcare and approach to community and approach to resource allocation. What have you learned from that? You’ve probably learned huge amounts, but what main teachings have you got from that?

Bob: When I offer my course on global health in Canada, the first question I ask my students is to define what is health, just to define. You’ll get a few answers that’ll come back. It could range from the absence of illness or to have good functionality as an organism. Some people will identify that it’s the broader conditions that maintain health and well being.

If any of your listeners have an iPhone or a dictionary on their tablet or computer right now, just punch in what’s the definition of health. It will probably come up in just a regular dictionary, the absence of illness. I find that very interesting because no other definition in the dictionary defines something for which it is not. You do not identify an apple as not being an orange.

We have structured so much of our attention on understanding what health is, as being the absence of illness. We really don’t understand what maintains and produces health in the first place. It goes far beyond bio medicine and it has a lot to do with social equity and justice, social movements and the ability for people to take care of each other. That’s a really important and under explored area for health and health studies.

Shane: Did the revolution in Cuba and the focus on community and … Do you think that produces that different philosophical framework?

Bob: Absolutely. When you look at what the Fidel Castro, Raul Castro, Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, those guys, when they got into that, it was about agrarian reform, it was about land redistribution. That was their movement. There were other movements in Cuba. There was an urban movement, there was a student movement, there was a communist movement. They all had different goals.

With the Cuban revolution, the first thing was land reform, and then education, and then health. It wasn’t until 1962 that Cuba officially nationalized its healthcare system. Now, it’s one of the greatest drivers of its economy. It’s opened up doors around the world, even to warm up relationships with the United States. Initially, it wasn’t the focus. The focus was to try to get access to resources and education for the poor, and then from there, build health capacity.

Shane: On reflection, is that the right order to do it in? I think a lot of people keep saying, how do you best promote healthcare? I think your dad said this, Sam, was about having educate first, and then the health improvements go in. Remember that conversation we had? Is that something that you would agree with? Is that order right?

Bob: Yeah. The fact that if you look at how our health systems operate around the world, they’re usually there to make sure that there is good employment for health workers and that patients don’t go bankrupt in the process. Most well functioning healthcare systems follow that guideline to a degree. Very few of them really look at health promotion and disease prevention in the same close net, well organized sense.

When you look at a lot of health promotion material, it’ll often deal with individual behaviour change. Don’t smoke, try to drink less, exercise, et cetera. Just look at the smoking factor, for example. You walk into a doctor’s office, they’re going to ask you if you smoke, no matter what it is. If you have a cut on your toe, are you a smoker? That’ll come up. We know that in most societies, it’s the poor, the people who are the lowest income brackets, are also the most frequent and heavy smokers. Why do we look at something like that in terms of individual behaviour change and instead of seeing this as an issue of equity, of demographics, of income inequity, of social equity?

If you re-approach the question that way, you may be able to find strategies that are more effective than simply putting up bus ads to encourage people not to smoke.

Shane: It really is very much community based, equity. What can the west learn from this?

Bob: Let’s go back to Cuba for a minute. Some people call it the Cuban paradox, where you’ve got such a low income on a national level compared to wealthier nations, yet their health determinates right across the board are fantastic. One theory is that the levels of income aren’t that great in Cuba. The person who earns the top and the person who earns the least, there isn’t that great of a differential between the two. There’s some research on that that came out of the Whitehall Studies in the ’60s in the UK that tried to look at how income differences matter.

Then evolving from that, there’s another theory that says that really, it’s about social equity, it’s about class and hierarchy, and your position to have sense of responsibility, autonomy and control over your livelihood, that that matters a lot more to health than differences in dollars and sense.

Shane: This is the work the Spirit Level Address looked at. Of course, they’ve done more research since.

Bob: Exactly. In the Cuban case, there’s a lot of evidence to show that because it has that relative level of social equity, they’ve been able to produce these health outcomes in a way where people have a better sense of health, and hence their health services are not invested as much as other systems are in repairing people, as opposed to maintaining that health. Now, with increasing inequities arising in the country, this could be something that will be a challenge that they’re going to face.

Shane: I was looking at the … You’re talking about sports for development and how it’s being used as a way of, in Cuba, to promote social equity and development. I reflected on, that sounded really like the GAA (Gaelic football).  In the sport and revolutionary movement skills, it reminds me of the GAA in Ireland at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century when it was really a front for the … A way of getting people involved in the Gaelic revival movement, and then obviously involved in revolution, their war of independence.

That’s really interesting. What did you learn from that? How does Cuba use sport, and what sports do they play?

Bob: What’s really interesting about Cuban sport is that you look at the Olympic medal county, Cuba and New Zealand are right next to each other, where they ended for medal counts. They usually punch above their weight quite a bit when it comes to elite sport performance. The other factor is that about 95% of the Cuban population at some point in their lives, participate in organized sporting activities. This could be off to a gymnastics school or a baseball camp, something in that way, or if you’re ever in Havana and you’re up between 6:00 and 7:00 in the morning, you’ll see these, they call them grandmother circles, where you’ll have the seniors coming out and doing tai chi and yoga in the park on a daily basis.

The encouragement that people are active in sport is a very strong national value in Cuba. It’s done in a way where you want to encourage as much participation as possible. Community level stuff where it’s participatory. Then from there, begin to offer streams for advanced elite performance. That’s very different, how a lot of countries, Australia and Canada in particular, groom their elite athletes. It’s usually, you take a lot of money and you invest in a few athletes who are likely to perform at certain sports well, rather than actually trying to draw out elite performance from national participation.

The other thing is that when you retire, if you’re an elite athlete, you still have an occupation with the Cuban ministry of sport. You become a coach, you become a teacher, you’re not unemployed looking to do something different when it’s done. You are still part of the system. It’s a lifelong career to be I sport in Cuba.

Shane: Do you think those systems will fall apart as it opens up?

Bob: What I find very interesting is that there will be some changes, of course, to Cuba. Where they’ve put their attention and emphasis in their development stream is by investing heavily in education and healthcare. That includes sport, sport’s a part of that. In the 1990s when they lost 35% of their GDP, 87% of their exports in 1992, 35,000 people went blind due to the lack of vitamins, the average Cuban male lost 40 pounds, that’d be 20 kilos or so, in a year. They thought the whole show was going to end.

Where most countries that were faces economic crises at the time, where they created this austerity that went into health and education in particular, Cuba expanded schools, expanded hospitals and expanded seats for medical students, and they offered scholarships for foreigners to come in as well. Fast forward 15, 20 years, and now you have at the forefront of their economic growth is a provision of healthcare services to other countries. Now you’ve got 36,000 Cuban health workers working in 66 countries around the world. In some cases, when they do partnerships with the Gulf states, with South Africa, they get quite a good amount of remuneration for that. When they partner with Haiti, nothing. They do it for charity.

The country of the Gambia, I love this one, where the Gambia had a malaria crisis in the early 2000s, late 1990s. They said, “We need to get on this. Cuba, can you help?” “Sure, what would you like?” “We’d like doctors.” “We think you need a medical school, so we don’t have to keep sending you our doctors all the time.” 250 Cubans come in, they build a medical school, they provide community care, they address malaria in this way where you had 600,000 cases in 2001 down to 200,000 cases by 2006, and now it’s under 100,000 cases a year, which is an amazing decline.

When they start talking about what can you give us back for this work that we’re doing here, Gambia, who was quite broke at the time, said, “Do you like peanuts? We have a lot of peanuts. We export peanuts. We can give you preferential trade deal on peanuts.” Sold. Then later, third country partners like Taiwan and Norway came in to offer financial assistance with those projects.

Shane: Wow. That’s incredible.

Bob: It’s a shockingly different way of thinking about foreign aid, about what global health is, and about the importance of actually creating capacity within communities, as opposed to just always doling our or giving out extra resources in that way. Those doctors who worked in west Africa and Cuba carried on, other delegations have come in. If you go back to 2013, 2014 when Ebola was kicking off in west Africa, it was the Cuban doctors who were already there on the ground, and then another 600 showed up to go into the red zone to be the only medical work force to provide that number of physicians on the ground.

Sam: You’re talking next week about researching a place you can’t go to.

Bob: That’s right.

Sam: What gave you that idea?

Bob: Here’s the connection between health and what we’ll talk about in a minute about North Korea, is that on one sense, on doing work on Cuba, people would colloquially just compare Cuba to North Korea, and then I would grumble and get frustrated. That was always on my back radar. When you look at how these advances in health promotion or anything, really, foreign, it’s usually by people demanding it. Well organized, committed individuals who make these demands for program design and for such developments.

I wanted to offer a class on social movements, activism and social justice, and I did. It’s one where we have students actually going out, hitting the streets, and protesting for concerns that they have. The university in Canada, they were a little concerned about what topics would be fitting. I was trying to guide people on topics where there would be no moral opposition. I read a book about the story of a defector from North Korea. His story, I devoured it and I thought, students are going to love it. We turn it over to them, they did love it, and they wanted to start protesting about human rights in North Korea, figuring who in the world would object to that.

Once you start seeing how grim that reality is, away we go. We were out protesting, aiming at world leaders who were coming to our city of Halifax for a security meeting, and we just said, “By all means, have your meeting, but if you’re going to talk about security, don’t forget human security. Let’s talk about people who are in need now.” We’ve done that for four years, and in that time, North Korean defectors have reached out to us for support, for opportunities to tell their stories, to do research projects together, and it’s carried on since then.

That switch over to this world of social justice brings me to working with North Korean defectors. The very difficult part about that is that North Korea is a no go zone for research, as I’ll be talking about next Tuesday. The amount of published articles on North Korea are shockingly few. There’s no topic that is this understudied. It’s a topic where it’s just shrouded in mist and rumors and deceit and intentional mistakes, where defector testimony that comes out from North Korea is usually incorrect. The satellite imagery is not as accurate as we would like it to be. The politics of this place, we don’t fully understand. Everything is a black box.

For myself, someone who’s publicly helped and supported North Korean defectors and spoken out against the regime, if I was to go there, that would be the end of me. It’s a place where you cannot go, but you know there’s something important to be studied and explored there. The question is, how do you do it?

Shane: that’s really interesting. You talked about how health is normally … Better health outcomes is demanded by the people, and North Korea is a communist country, and so is Cuba. You’ve already said …Â communist countries. First part of the question, did Cuba, was that focus on developing healthcare, was that done by the leadership or by the people, and the second question is, what is the primary difference between Cuba, which has done this amazing thing with its people, and North Korea, which seems to be doing terrible things to its people.

Bob: Absolutely. The first question is about where did Cuba’s medical system come up. The real foundations to it were in 1962 when they passed a bill to say that physicians could no longer bill patients directly for medical services. Mirroring exactly what happens in the UK and Canada and elsewhere, and even proposed by the Kennedy administration at the time in the states. It wasn’t too radical by any means. The physicians in Cuba took off. Of a workforce of 6000, they were suddenly down to just under 3000. You had 256 teaching faculty at the University of Havana in 1962, by 1965 you had 14.

That exodus of that medical expertise, because Havana was well known for medical expertise in the ’50s and ’40s, left this void, this vacuum, of a new generation of doctors and medical students that built the system up based on the values that you have today. It wasn’t ever put in the hands of the top leadership to say we have this miracle vision that we’re going to drive it. It was always about impact and feedback from both physicians and patients in communities to meet their needs. It’s been a very elaborate process.

This is where you see that to label something as just communist, may be accurate in terms of how their government’s organized, but there’s a lot of flavors of communism, from the mild version to the absolute toxic. With Cuba, you see that they’ve always had this ability to have feedback from communities to the representatives in government. Sometimes it’s slow, there’s a lot of inefficiencies within there, but there is that value of human security that comes out.

When you look at North Korea, a country that leadership in Cuba did not visit until 1995, “We don’t want anything to do with these guys, this is a different flavor.” It came up almost by accident, where you had a leader rise to power, Kim Il Sung, who read the Stalin Playbook, same thing that happened in the eastern states in Europe, where that form of governance was about trying to create a cult of personality, kill your enemies, kill your political opponents, and get orders top down.

You see it almost operate more as a feudal system, where you have this elite in Pyongyang that want for not. Below them, the loyal class who are pretty well taken care of. Then, they have a wavering class and a hostile class. That’s literally what it’s called. It’s called the Songbun system, it’s a feudal form of control where you have those three major classes derived in about 50 or so subgroups. The government there realizes that most of the people that are under its control resent it terribly, and there are these systems of control in place wherein if you speak out against the leader, it’d be considered a political crime, you will be going to a political prison camp. Your family will be going to a political prison camp. Any children you have will be going and any children they have will be going as well. Three generations of punishment.

Nothing that nuts has ever existed in Cuba, even in what they call the four gray years, the 1970s, where if you spoke out against communism, you maybe had long hair and listened to rock and roll, you’d have the moral authority police come over and give you a stern talking to. There is some determinant that also took place in Cuba in the ’60s and ’70s for people who deviated. Now, no. That’s about as far away as it can get. A lot of scholars in cube recognize how twisted the North Korea system is.

It’s a different world.

Sam: I’m going to change topics slightly. You talk about deviation. You teach a course, which is called Development and Audacity.

Bob: Yeah. Audacity development, development activism, yes.

Sam: How did you manage to convince the university to let you teach something with that title?

Bob: Yes. Just to be clear, we’re talking about my university back in Canada, Dalhousie. When you offer a course as a one off, nobody really pays attention to you. Special topics. Then if it gets popular, as this one did, and we took it not just from a one off topic, but to a calendar course and then a degree requirement. Then that sat before a committee called the Academic Development Committee where they had visions of students running riot in the streets and just losing it.

I got called in and the dean is there, and other members of this committee are they. They start asking questions about, “What happens if there’s a radical takeover of your class by a fundamentalist student?” I said, “I guess we call the police.” “What happens if a student wants to burn a police car?” I said, “Look, I don’t know how to do that, contact the chemistry department. They’re the experts.”

This banter went on back and forth and I said, “Look, you guys are missing the point. If you look at history and you look at the history of social movements, universities have always had a fundamental role in that.” When you had students in Tennessee and Mississippi taking over lunch counters, they were organized, they were taking seminars on nonviolent resistance. It was faculty who were leading that. You see this from Martin Luther to Martin Luther King Jr. There’s always been this association of higher learning to progressive social movements. The women’s suffragettes in the US in the early 1900s, all university students. The guys who kicked off Tahrir Square in Egypt, university students. The guys who overthrew Milosevic, university students.

Instead of saying that this is something that happens on the fringe of university culture, why can’t we make this a learning experience? Again, people dithered on it and they weren’t too sure, but ultimately, when you have a class of 35, then you have to expand the enrolment to 60, and then 75, and then 80, it becomes very financially attractive for the university to make sure that course stays on the books.

Shane: Did it end up being a degree requirement?

Bob: Yes, it is.

Shane: Can you require all students to be an activist?

Bob: Absolutely not. By no means is that course the minting process to be an activist. What it is is it gives students the opportunity to engage with it in real time, to look at what goes into the organization of a social movement, to create a scenario that we’re going to go out and make our demands known to people in government and try to get the attention of others in society. That doesn’t just happen by swinging a picket sign around on a crowded street. We have to plan about this, we have to think about it, then we have to reflect on how this is impacting our politics today.

Why are some social movements so quick to be recognized and embraced and others quickly dismissed? It gives students what we call experiential learning. The ability to witness, experience and engage in this process, and then form their own structured thoughts that connect the literature to that experience. That’s really it.

There’s been cases where we’ve had students from the military who are under Canadian military code cannot protest. They can’t do it. How do they get through? We set up roles for them as researchers if they want. Others who have objected to it. Students who come from South Korea who are on a working Visa and they say, “I don’t want anything to do with messing around with North Korea, man. This is too hard.”

There’s always accommodating at every turn. That myth that activism and social movements are somehow naturally organic, that they don’t require leadership, that they don’t require dealing with interpersonal skills at a community level, that’s a dangerous knowledge. If we realize, we really realize that if you have a small group of well organized people put together, and be they’re committed to it, you can intimidate a regime like North Korea, in places where other governments have failed. You can demand things like better equity, better social justice, better healthcare.

It’s a very, very powerful force, and most world leaders, governments, businesses, are quite intimidated by activism. In one sense, it can be a very powerful tool for change, it can also be something that can go right off the rails and lead to far worse consequences.

Sam: If you could have a whole degree in it, would you do it?

Bob: I think that idea would be fantastic, but we would need a big team of teachers and experts to get through that. We would need philosophers, ethicists, city planners, historians, the geographers would be in there somewhere, of course, to really understand how this process impacts our world.

The other thing that’s really challenging about activism is that in that moment, when something is conflicted, there’s a tendency to label activists as being the outlaws, the troublemakers. Then you look back at history, the heroes of the day now were the outlaws of the time then. That’s a very difficult thing for society to accept.

Sam: Given that most of the students I would suggest aren’t going into societal roles where they are carrying on being placard waving activists, and lots of them are going into various businesses or government. Do you talk to them about how they can carry on that role?

Bob: Absolutely. We’ve had students come out of that class and have run as members of parliament, they didn’t win but they did it. That was good. The practical skills that come from this course are quite strong. They get into issues of advertising, marketing, campaigning, all of that. There’s a lot nongovernmental organizations and political parties who find value in that practical skillset. We all know that university education is beyond just practical skills, it’s about opening your mind to alternative ideas.

The feedback I receive from students down the road, who graduated the course, maybe they’ve gone onto a higher education degree, maybe they’ve gone into corporate sectors, some people work for law firms. They’ll write me little anecdotes to say that there are moments in their professional careers where they disagree with something, they disagree with authority, they disagree with how something’s being run. Instead of just ranting or grumbling by the water cooler or voting with your feet and leaving, they’ve actually been able to strategize, to create small change, even within their own workplace.

Others have, I hope, learned some of the value in organizing at a community level with issues that might be impacting their world.

Sam: Do you have a go-to definition of sustainability?