It starts with talking and it starts with doing things ever so slightly differently. Those sort of little incremental changes allow people to start just even just shifting the way they’re thinking and making space for doing things differently.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Our guest tonight is Dr Sophie Bond. She’s a senior lecturer in the Department of Geography at Otago University. Her areas of research include the formation of collectives in response to environmental and social change. Social sustainability, autonomous geographies, and alternative economies, urban sustainability, qualitative and feminist methodologies, political ecology and discourse theory. Welcome to our show, Sophie.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Thank you.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Now, just before the show I can embarrass myself as always because you guys said that you went to school with Sam. I thought because I heard that southwest English accent the same accent Sam has. I thought you went to school in England, but you didn’t. You came from very close to where Sam grew up.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I spent the first four years of my life in Bristol.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Funny, I can still hear it, just a little bit. I’m a linguist so I pick these things up a bit more quickly than other people. Do you remember much about Bristol?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I’ve been back a few times, spent quite a bit of time there. My partner is from Dorset so we try to get back there quite regularly.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Oh cool. You grew up in Dunedin, is that right?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s right, I grew up here.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â They have a great school I might add.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What school is that?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Logan Park.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Logan Park where my son goes as well and Sam’s son.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â My daughter studies there too.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Oh yeah, it’s a crazy place. You went to Logan Park. Was there something at the school that got you interesting in geography or … What got you interested in going to university?

Sophie:                Actually I came at geography in a very, very roundabout way.  I did a law degree as my undergrad. I did women’s studies. I wasn’t remotely interested in geography at that time. Then, had a bit of a break went to, lived in Monaco for awhile, did some stuff there. Including getting involved in the environmental society writing, submissions and helping them out on a few things. Then, we were abroad for a couple of years, came back and deciding that we do something a bit more productive than what we were heading. Went to back to university, and did a planning masters in the geography department and then kind of stayed. Got a PhD. following on from that. Yeah.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What got you particularly interested in the sustainability stuff? What was the urban sustainability? What got you interested in that? I noticed your PhD. and thesis, we’ll talk about that a little bit later. What piqued your interest about that?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think it was … It’s really hard to pinpoint. I think I’ve always been interested in environmental issues. I think also, my focus on sustainability has always been in relations to social sustainability and I guess urban sustainability was a way to focus on the social in the context of a very sort of physical environment planning system here. Planning stuff kind of drew me into that urban sustainability stuff I think.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What’s your legal qualifications, do they help with those concepts about legality and governance and …

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, I think they did. When I did my law degree I focused on peripheral subjects not mainstream law subjects, like environmental law, international law. Some of the public health stuff and ethics and things like that. Yeah, definitely.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Would you characterize New Zealand as being quite advanced with the resource management act at that point. At that stage, was it a bit kind of ahead of the game and thought it was exciting?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think the reform process, the resource management reform process and the way that it brought lots of different groups together to discuss the issues was well ahead of its time. I think the way it’s been rolled out and practiced has closed down a lot of those opportunities that initially started with the focus on sustainable management. It was a first, I think, for many countries in terms of focusing on their sustainable management in terms of it being the main planning legislation. Yeah.

Shane:                 That provided a lot of areas for research. Did you find anything interesting about that? Was there any particular reason why it happened here in New Zealand first? Or did you have any understanding of that? Was it just that …

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think the 1990s reforms here were so aggressive in terms of sort of embracing the umbrella-ism that we were in a state of flux and a state of change anyway. That might have provided some of the conditions for that. Yeah, so they were reforming local government at the same time. I think that probably had a huge impetus. Yeah, it’s not an area that I’m hugely familiar with. I’m just yeah.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What’s an autonomous geography? That’s another phrase, I went, What is that?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Autonomous geography, it’s a group of researchers in the UK who were … They describe themselves as activist scholars. They’re really actively involved in creating change through their own scholarship and through their own activism. They bring those things together as much as possible. Autonomous geography has kind of embraced part of that idea, so a lot of their research has been about creating social spaces or community spaces. They’re trying to create alternatives to business as usual, the status quo and be sort of autonomous from mainstream consumption and that sort of thing.

Autonomous geography is about looking at those spaces and how they operate and how they create change for the people who are living and working within those spaces and that sort of thing. I guess you could include things like time banks, community spaces. They have a number of different operations going on within them. Alternative economies, things like some transition towns would sort of embrace those ideas as well. They often operate on a non-hierarchical consensus building type of consensus based decision making model as well.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Sounds very near anarchist.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Very much informed by anarchist thinking, yeah.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Just to be clear, though, do you consider yourself to be an autonomous geographer?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Why not?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Probably because at the that stage I’m at I don’t think I’m quite fully embracing the way that they embrace those concepts, living it and doing it. I’m working on it, but I’m definitely not there yet.

Shane:                 Moving on to the next interesting topic there was qualitative and feminist methodology, in order to put those together, why did you put politics and feminist methodologies … A lot of people may be asking what does feminism got to do with geography. I kind of get what it does, but why are those two things together and how does feminism inform geography, understanding geography.

Sophie:                There’s a huge area of feminist geography within human geography, within the geography of people and place. The sort of more social geographies. Actually, feminist geography is a discipline or sub-discipline has been really instrumental in creating opportunities in making qualitative methods acceptable and rigorous and an important part of social science. They did that by questioning a more scientific method, which has its place but also misses out a whole lot of the human experience. The emotional aspects of being and living in the places that we exist in. I think feminist geographies are not just about looking at gender as a form of inequality, which they do a lot of. How gender inequality is distributed in different places, and how they exist in the power relationships associated with those things. It’s also about thinking about how knowledge is produced. How research is responsible for the knowledge they produce. Actual research as a co-production of knowledge, it’s not just about experts coming in and extracting knowledge from groups or from people. It’s about working with communities to produce knowledge in a shared way. Treating people as the experts, the communities that we work with are the experts. We’re sharing knowledge building processes and doing work that those communities and those groups are wanting to have done. That it’s going to feed into things that are useful for them.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â A lot of sustainability thinking criticizes quantitative research and the scientific method because it misses out the human experience. It misses out … You can only use proxies for instance the health of streams. You can say, it’s got the [neoduction 00:09:40] levels of this, the [duction 00:09:42] levels of that. You can talk about bio-diversity, but even that’s kind of controversial. Subject now, that definition there, is that criticism the same as feminist criticisms, that science can only give you approximation or a proxy indicators of what’s actually there. That it misses out on this massive thing, it disconnects us from nature. Is that …

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, that’s a really big part of it, it’s partly it’s that objective knowledge that you can … It’s like with the scientific method, the scientist is invisible. The knowledge is produced. The scientific method is so far normalized as the means of the main dominant means of producing knowledge that we don’t question the decisions that are made in the process of producing that knowledge enough. What feminist geographers were trying to do, and has happened in other social science disciplines as well, as well as other feminist sociologists for example and others. They were trying to say that we need to recognize that any knowledge production process involves making a whole series of decisions that may include or exclude certain factors and certain assets of the nature of the proxy that’s used to measure whatever. Has an effect on the outcomes. It’s about being really critical about who is making those decisions and why they’re being made and how they’re being made. What the effect of those decisions is. It’s just about questioning the process and not treating science as some absolute, you know, sort of single truth, you know.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s not a universal truth. The thing is, what people forget when they tend to be like … When scientists pretend to be invisible is that they choose the questions. Those questions are framed by their world view. This was the feminist critique …

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Absolutely.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Saying hey you come to this space with a world view. You might go into a native tribe in the middle of the Amazon and say, “These people are really primitive, they don’t know anything.” They have a huge wealth of knowledge, but it’s not knowledge that’s recognized by Western science. The knowledge of the environment so that’s really, really interesting. Let’s go on to political ecology. What is political ecology?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Political ecology is kind of the molding together of ideas about political economy. Almost processes of production, reproduction, roles catylism, within, marrying with the idea of ecologies. Ecologies being networks of systems that involve people, places, environments and so on. It’s a really diverse area. It involves social anthropology, development studies, geography, sociology, loads and loads of different disciplines. The level of sort of scientific ecology that comes into those political ecologies is really variable. Actually, probably more recently it has moved more and more and more towards the social sciences. It’s about looking at the relationships between the actions that people have in particular places and their effects on sort of broad ecologies.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â You said social economy there. The current paradigm, the dominant paradigm is that politics and economics, they have to be kept separate. You said social economy here, so will you talk about that?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I’m not a political economist. Yeah, I guess using political economy probably coming from it from its Marxist roots rather than thinking about it as the political system is, at the moment, which is embedded within neo-liberalism. I guess the broader idea behind political ecology is to demonstrate that those broader economic drivers have a fundamental shaping effect on the decisions that are made and how we interact with environments.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â The last thing was discourse theory, so could you explain what discourse theory is?

Sophie:                Discourse theory is,  a specific analytical tool that actually comes from a group of scholars from the University of Essex in the school of government. It was initially developed by, primarily by two people, Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau, who were pretty famous for a book they wrote in 1985. They’ve been described as sort of post-Marxist thinkers. They’re really talking about ideas about democracy, very broadly conceived and how power shapes what people can say in particular situations. Discourse theory draws on this idea, sort of a [DeCodian 00:15:12] idea of discourse, discourse as a set of ideas that shape how things are understood in the world and how meanings are made. How this then becomes hegemonic or dominant and normalized, so that we don’t actually see outside it. This is the case, many would argue, in terms of neo-liberalism. Unless you’re really critical of it, you probably don’t call it neo-liberalism. You also don’t see beyond the role of the market or creating jobs as a good thing. Those sorts of things that are embedded within the sort of contemporary, business as usual, model of capitalism. What discourse theory allows is a kind of way of thinking about and picking how particular sets of ideas coalesce around a key idea or key concept and then they are perpetuated and continued through a whole series of power relations in society.

Those power relations go from things that have happened in the media in a way that media perpetuates it as a way of understanding the world all the way down to our individual actions. How we’re shaped by the meanings that are made and represented to us so we continually perform them and re-perform them and reproduce them through those performances as well.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â One of the interesting things that I’ve been thinking about is that in the Great Depression during the 1920s, there was a huge amount of discussion about capitalism and the nature of capitalism. Then, we had the 2008 global financial crisis and there was some discussion. There were many movements, like the Occupy movement, [inaudible 00:16:56]. The Arab Spring was a direct result of the repercussions of the GFC. Do we have any handle or any understanding of why those movements haven’t flourished or why they’re … That they haven’t quite succeed in the way that … You can look at 1930s Europe and America, there was a huge foment of different ideas and new concepts and debate. Which had some very aspects as well, nervous if that happens. We seem to just have fallen back into the pre-2008 time, mind frame. Is there anything like … You talk about alternative responses and social responses, that was a big alternative of social response so what happened to it?[crosstalk 00:18:02].

Sophie:                It’s such a hard question. It’s big, it’s huge. I’ve got some ideas, a lot of it’s embedded within the way that … I’m going to come down hard on neo-liberalism again. The way that neo-liberalism is so dominant and hegemonic. I think I’ve done a little bit of digging around some of those earlier ideas or those early thinkers in relation to neo-liberalism ,a guy called Mirowski, who is a leftist economist, has written a book and done quite a lot of work. He talks about the neo-liberal thought collective. You know those early thinkers, Hayek and Friedman and so on. They have created this collective, who were very tightly knit. They were trying to create this ideology and get it going. They were really forceful, really strategic, and really clever in the way that they did that. It took them until the 1980s before it started being rolled out in different places around the world, the States and in Britain under Thatcher and here.

One of the things that they did, this is something that Mirowski writes about, they had this idea that actually in order to have neo-liberalism work, you’ve got to have a really strong state. Which is counter to the neo-liberal mantra of a de-evolved state and de-evolution and de-centralization. They knew that to have a really strong state, particularly in the context of the time that they were talking about this and building this momentum, which was 1940s, 1950s was really unpalatable. They also saw that in order to have this strong state, you couldn’t have … democracy was the antithesis of being able to roll out neo-liberalism in the way they wanted to. There was this disconnect between the power of the people and rolling out this project of neo-liberalism. They knew that was really unpalatable so they hid it. They turned the ideas of democracy into freedom of choice and freedom of consumption. It was a kind of a really clever kind of move, now our political practitioners and political scientists could perhaps have done some work on this. He has said, he’s done some work where he’s talked to governance practitioners, people who are working in the governance and the ministries and in government and local government.

There’s this idea that actually real democracy doesn’t give democratic outcomes, doesn’t give good policy. Our practitioners in government don’t believe that full participatory democracy or debating issues or discussing issues is actually going to produce good policies. This has become this kind of entrenched idea I think within our governance practitioners. How do we create change when the people who are supposed to be the people who are leading us in democratic forms in democracies, don’t believe in it.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What would a full participatory democracy look like, then?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I don’t know. No, I don’t know. I guess an ideal that would certainly be better than what we have at the moment is spaces for robust debate about issues. Whereas, at the moment, we get closed down by any thing that kind of is dissenting against the sort of business as usual. There’s debate about stuff round about the middle, straight down the middle, that doesn’t really go against the main system. Anything that goes against it or outside it is “you’re just a leftie,” or a hippie or a greenie, so we don’t need to worry about you. There’s a kind of like this de-legitimization, a systematic de-legitimization of anyone who’s outside that mainstream, straight down the middle.

Shane:                 This is incredibly topical because right now there’s a protest in town about the TPPA, which is the TransPacific Partnership Agreement, which is being sold as a free trade agreement, but it isn’t. Because the stuff that’s been leaked we can see it’s all about corporate control and investor state disputes. There’s been a power grab by the corporations so this obviously involves a lot of double think. To borrow George Orwell’s brilliant term. TPPA is like another step in that process of de-democratization and grabbing power.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Absolutely. It’s a classic example of it. Yes, it’s quite scary.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I didn’t realize … I knew there was a TPPA or a TPIP or PPI in Europe so there’s a previous one between the US and Europe. There’s also the TSA one as well, which is the trade and services agreement. TSA is also being negotiated. There’s three negotiations at the same time, kind of roughly overlapping, kind of doing the same kind of stuff. Where we’re giving up our power as democracies to set our laws to corporations. People are dismissing the protesters in exactly the same way as you’ve described. Some people are angry protesting and re-route the protest, but what about the mainstream people. Do you have insight why people just aren’t kind of … Is it complex? Is it too complicated?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s complicated. There’s not very much information about it. The information out there is leaked before it can be dismissed because it’s just leaked, it’s not official. I think that’s another big thing. There’s no open debate or discussion about it, you know. I think that there’s a lot of anger about it. I think there’s a sense of they’re going to do it anyway. We can’t necessarily do anything about it. I think what is positive is the number of people who were out the other weekend, all across the country

I had to have a wee chuckle at John Key’s responses to that where he started labeling. A third of them were Green … He didn’t actually say Green Peace fringe crowd. He did say fringe crowd. Another third were … He has these ways of basically de-legitimizing any protest. He did the same sort of thing with oil-free protests that were going on a few years back where there were 5,000 people on North Island beaches doing a banners on the beach type protest. He described them as a Green Peace fringe crowd. He has these one-liners and other ministers do too. The media picks up on those rather than going with reporting on the number of people who were there and the range of different people from all sectors of the community who were there as well. I think there’s a whole …

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Sustainable future is going to need a system change. Is it going to need the system to change to deliver it?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It is too hard. I agree a sustainable future does need a system change. I don’t know how we get there. I think, you know, we just got to keep trying to create change and create spaces where people feel empowered to speak out.

Shane:                 You discuss communities of change and how people come together, it is quite difficult to do that when you feel officialdom, the official society, is opposed to you or doesn’t agree with you. How communities get the courage to step up and …

Sophie:                That’s a really hard question too because all of those systematic methods of closure and this is part of some research that I’m doing at the moment is talking to people who are actively engaged in trying to create spaces of debate, dissent, and of action. Trying to work out how they deal with those constant negotiations that they have to deal with every day of being sneered at in the tea room when they have to get a cup of tea. Because they happen to be on the front page of a paper in a protest and they were seen there. They are like, “You were over there at the weekend you know.” Or “Are you happy?” Something like that. Which is seeing it in a really negative way, rather than something …

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â A celebration, yes you’re great to participate in democracy, You’re a great citizen.

Sophie:                Yes. Why doesn’t that happen more? I don’t know what the answer to that is. I think there’s a whole lot of pressures on us every day, as well as just being super busy and struggling to just keep going. It requires energy and motivation and the ability to counter that constant de-legitimization of what you believe in.

Sam:                 We went to Oamaru and did six interviews with various people from the transition town movement. In fact this trip of ours was prompted by you going the month before with the third year geographers – including my daughter.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yes.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â One of the things that was apparent to us was that there’s a really small group of people actually making a change on behalf of and taking the rest of the town with them. W interviewed six, there’s probably another 20 or so out of a town, I don’t know what it is, 10,000.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 10,000 yeah, 12,000.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Some of them had very much this attitude of yeah we’re taking the whole town with us, everyone thinks we’re great. Other people came in and said Hold on, most of the town thinks we’re loonies, but they’re recycling their rubbish. They’re visiting the community garden. Despite the fact that a whole lot of the town doesn’t think they’re a good job, they are actually reaching that tipping point. Is there a model that we can learn from in places like Oamaru, a Transition Town, for how we can make change without needing to convince absolutely everybody.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Absolutely. I think those small scale, local community responses that are creating opportunities and different kinds of relating to each other and relating to place and doing things differently are just absolutely vital. I think they do really, really important social stuff as well as really important environmental stuff in terms of building resilience for want of a better word. Creating connections between people that wouldn’t otherwise exist because people are too busy jumping in their car and going to work rather than walking down the road and chatting to people, or buying locally or whatever.

I think those things are really important. Actually, I think that’s one of the things that a group of scholars are doing in Australia. They’re called alternative economies network. They’ve done a huge amount of work on trying to understand both the social and environmental sort of ethics of these kinds of groups that create change from the ground up.

Sam:                 Marion Shaw, who runs the resource recovery park in Oamaru had a very clever line, which I can’t remember exactly what is was, but it was something like, “We’re in the business of recovering people, we just happen to be sorting the rubbish.” For me, it really brought home that community as the centre of the sustainability message. What’s your take on the relationship between community and sustainability?

Sophie:                I think it’s fundamental. I don’t think you can have environmental sustainability without having communities who are embracing social sustainability or embracing and relating and working together to achieve it. It’s never going to be a top down thing. People aren’t going to respond to [inaudible 00:30:30], though they would be helpful in some contexts. I think, you know, encouraging people to work together to create change is one of the best ways to achieve the kinds of things we need to start achieving.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Why do we value some work over other work? This probably comes back to feminism and in fact I’m absolutely positive that it comes back to feminism because most of the highly paying jobs are done by men and not by women. I don’t think that was a coincidence, or that there’s any reason for it. How do we establish these value systems and why …

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â There’s messes. I don’t know. I don’t know. I guess one thing to hold onto is that these value systems get created, but they’re not absolute. They can be changed. I think it’s the sort of thing to keep holding onto. It’s just like, there’s definitely something to be said …

Shane:                 As far as when you look at alternative economies, are there other systems or other systems of economies that we can look to. For instance, as an example, the Iroquois Nation had a completely different economy to Western Europe. When people arrived there, they shared resources and a women’s council basically divvied out all the resources according to whatever system they had. That was a completely different system to what was happening in Western Europe at the time when Westerners arrived in North America. Are there other alternative economies out there that maybe we can look to as maybe positive examples. Have you come across any?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I haven’t really. It’s an area I would like to look into more. I mean there’s all sorts of models all over the show that wold be really useful to tap into. I guess it’s again about creating the spaces to experiment and try out different forms of economic exchange that don’t involve the [inaudible 00:32:49] economy. To value those kinds of labors as you suggested before in different ways.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â We’re almost doing that. We’re doing that in transition towns. Oamaru is doing it. There’s this alternative economy going on. Which is not about money exchange, it’s about exchange of skills, food.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Time banks.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Time banks as well. That stuff all. It’s happening …

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Time banks. I was talking to students about it today. Time banks is just about how much time it takes you, isn’t it? If you’re a brain surgeon or baking a cake, it’s an hour’s worth of time.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, the media is time. Yeah, the market is based on time.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Do those hold up over the long-term?

Sophie:                It depends, to some extent, on the nature of the group who are involved in the time bank, I think. People who are willing to engage in that exchange on that basis will do so. People who aren’t won’t. I guess, in a way, it’s a kind of flattening out, a kind of radical form of equality in terms of valuing time in a completely sort of flat way. There’s no hierarchy involved anymore. Perhaps there is a hierarchy but it’s reversed because those task that people don’t want to do are the tasks that people want done, so they’re actually valued more highly than are the highly skilled jobs. Actually, maybe it changes those hierarchies quite nicely. Time banks operate on different bases, I think as well, it depends on how they’re set up and that sort of thing.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What’s your go-to definition of sustainability?

Sophie:                I don’t really have a go-to definition of sustainability. I think it encompasses ideas of that sort of nexus between social and environmental sustainability. I don’t think you can have one without the other. It’s about creating some kind of, I was going to say, equilibrium, but it’s probably not quite what I mean. Something that’s just more, something that’s just more caring in long term.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â You keep saying social and environmental sustainability, as if they’re two different things. Are they?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No, no, no they’re not. It’s probably because when I was reading sustainability literature, that’s exactly what they were treated as. I think the other thing is the whole … Sustainability is not actually a term I use very often. The reason is because often it just ends up meaning economic sustainability, which is not where we’re coming from at all.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What do you use instead? I’m here with my pencil ready to write it down.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I talk about alternative futures, probably.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s funny because no one knows what that definition is. Thank you for asking.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Nobody has one, that’s a relief.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What about resilience, we’ve got that in the title as well.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, resilience is another one that’s going the same way as sustainability. It gets co-opted in all sorts of ways where it loses it’s sort of critical egalitarian purchase.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Is it radical enough?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Exactly, I think the way it’s often used, it’s not. It doesn’t, I don’t think it does enough.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think it is used because it is more appealing. We don’t actually have to change anything, it’s just about a few community gatherings. We’ll be all right.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, that’s right. Â It’s about adapting to change, not creating change, yeah.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What successes have you had in the last couple of years?

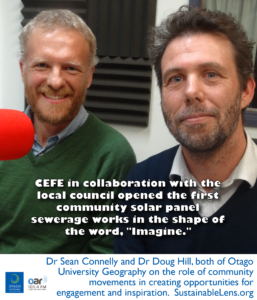

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Actually kind of bring together the stuff that I’m researching with the stuff that I’m teaching. Trying to create change through those things I think is kind of the main thing. For example, Doug Hill and I created a course in geography and taught it for the first time this semester last year. It was about creating spaces of contestation within the context of neo-liberal New Zealand. It was about drawing together some of the things we were talking about before. How democracy is shifted so radically and try to bring it back. That’s sort of where a lot of my research is at the moment as well. That’s probably … It feels very modest. I’ve been here for two years, I haven’t been away for quite a long time and I’m just still finding my feet. Working on creating other opportunities.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â You say that you’re not an autonomous geographer despite the fact they have activist scholarship. Do you consider yourself to be an activist?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Not really. I would probably say that I’m probably a want to be. Â I do research with groups who are activists, but I wouldn’t call myself one. I haven’t quite managed to work out how to commit the time to it and balance it with all the other time commitments at the moment.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s a time issue, not a philosophical position?

Sophie: Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s a time issue, not a philosophical position.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What would have to change?

Sophie: Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Academia being slightly less demanding on my time. That’s probably the main thing that would have to change.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â They do pay you.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â They do pay me. Yes, they do. They pay me well. I like to know that.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Following up from that then, I’m going to dismiss that as a motivation, what motivates you?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Issues of injustice.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That was quick.

Sophie: Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s the biggest motivator.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Has that always been a driver?

Sophie:                Yes, it has. That’s probably what I should have said when you asked me right at the beginning about sustainability, issues of injustice. That probably actually started from when I had a trip to South Africa in 1983, or 4. Pre-the end of apartheid, and it was quite an eye opener for an early teen.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What challenges do you have in the next couple of years?

Sophie:                The biggest challenge is probably actually being able to do what I want to achieve in the time constraints that I have. Time’s quite a big factor at the moment. I think trying to create a balance between being able to create opportunities for change and actually keep sort of doing the work that I’m doing in my day job in balance. Because I’m really not good at balancing at the moment. I struggle.

Sam:                 Okay to do less things, create opportunities for change. Lets start with what changes? What kind of changes do you want to see?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â The biggest change actually I want to see is coming back to those ideas about democracy. People feeling empowered to speak out and not de-legitimized for doing so. Not struggling with negotiating, constantly being harassed for doing so. Those are the kinds of things that I would really like to see shift. Because I think that would make a big difference.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â In any particular community or just in general?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â In general, I think.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Starting with the whole world.

Sophie:                No, no, no obviously. Starting with local communities in terms of working with local communities to try and achieve those sorts of goals. Or just actually working with local communities to identify the barriers that stop people from achieving those goals, as a first step. Then, trying to work out strategies for dealing with it.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â If you start with any old community, as one of the ones living down on the harbour, you can have Carey’s Bay, if you like.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Thank you

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What would you see actively happen differently?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I’m sure that there are really strong connections between many of those communities. I don’t want to sort of label anyone in particular. I think what you were talking about in terms of Oamaru and Transition Town stuff, creating connections and getting people talking about stuff actually is a huge motivator for people actually taking action. It starts with talking and it starts with doing things ever so slightly differently. Those sort of little incremental changes allow people to start just even just shifting the way they’re thinking and making space for doing things differently.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â You say incremental changes. One of the things I’m questioning is whether incremental changes are going to get us there. If enough of us change the light bulbs, actually that’s not going to help.

Sophie:                I agree with you. They still got to change. People can’t, I don’t think people can change fast in the current situation, which is kind of depressing.  I think people are so sort of… within the way we live our lives. The way we’re structured to continue to live our lives. There are so few people who have choices to be able to do things radically differently. A lot of people who do, do, which is great. You know people still have to go to work and do all that stuff and that’s just, you know. I think that there’s …

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Is radical change some sort of luxury then?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think it is a privileged position, at the moment, absolutely.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â It’s a privileged position that lots of people are happy being n that privileged position.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, that’s right. It ‘s a bit of a problem there.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What do we do about that?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I don’t know, re-distribute wealth.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s not going to happen.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I know.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s why I was saying a particular community. You’re not suggesting going and breaking down the doors of the manor house.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No, no because, yeah, I don’t know what the answer to that is.

Sam:                 Okay, if you could wave a magic wand and have a miracle occur by the time you wake up tomorrow morning, what would that miracle be?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Can I have two?

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â The first one would be that governments would divorce themselves from the corporate … That would be one that I think would make a very big difference and start looking beyond those three years …

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â They might pretend, but they’re not.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yeah, but they are. Actually start looking beyond three year terms and exponential economic growth. That would be my first one. The other one, as we were just talking about …

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That was already three, not two.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â that’s actually …

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No, that’s just one, okay.

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s just one big one, one big miracle. Then the other one is those community responses where people have the time and the energy to do all that fantastic stuff that people in transition towns are making happen.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Okay for the first one and the second one then, what’s the smallest thing that you could possibly do that would make the biggest difference in making that happen?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Say that again.

Sam:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â What’s the tiniest thing that you could that would have the biggest impact in terms of actually getting governments to divorce themselves from corporates looking beyond year three exponential growth? Sounds like three to me. What could we actually do to make that happen? … No, okay, it might be easier for the other one. What can we do to encourage community responses?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Talk to your neighbor.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â How can we scale up what they’re doing in Oamaru and places like it? Can it scale?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â I think it can replicate. I think as soon as those communities get too big, it starts to get really difficult to manage the sort of local dynamics that go on within any of those kinds of groups. Lots of groups scattered around that are working together. Lots of little communities, transition towns, or whatever they are. Yeah, I think it’s about understanding how they do things and working with that to create visions for possible alternatives.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Lastly, I have a list here you see. Lastly, do you have any advice for our listeners?

Sophie:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Be the change you want to see in the world.

Shane:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â That’s great, be the change.